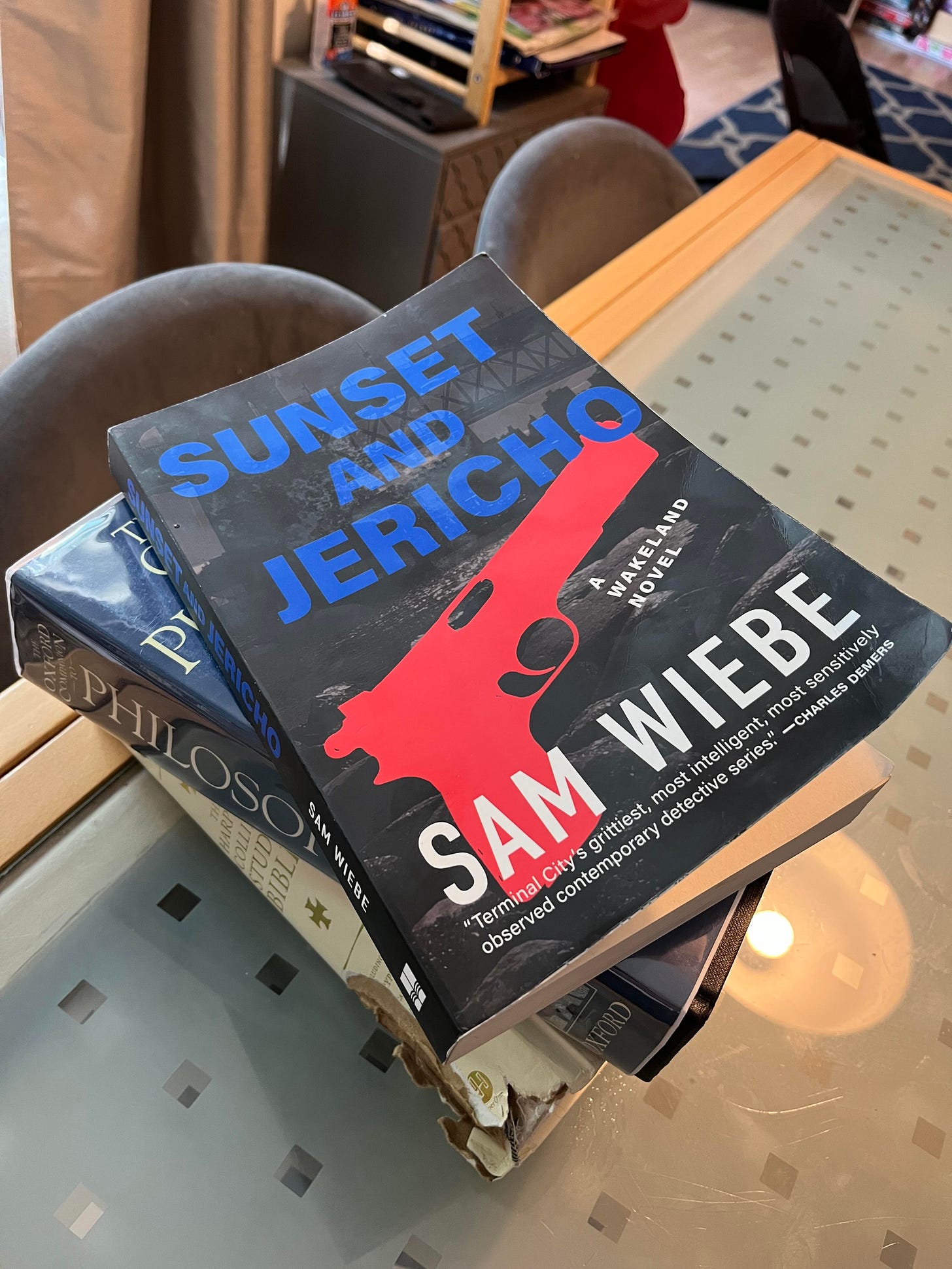

You can't handle the Truth: Sunset And Jericho

Sam Wiebe's secular religious detective novel asks the big questions

Disclosure: I am about as compromised as I possibly can be in writing a review of Sam Wiebe’s work. He’s a good friend, sometimes-collaborator, we’re at the same literary agency, & our publishers are owned by the same people. If you read this weirdo religio-philosophical review of his new book & think I’m doing it venally… you at least have to grant that I’m bad at it.

Since especially the days of Philip Marlowe, the literary private investigator has occupied a very particular space in relation to questions of ethics and morality. On a superficial level, the PI is a moral skeptic, the man (or, less frequently, woman) for whom all social, institutional, and official hypocrisies are totally transparent. He doesn’t wear any uniforms, swear any allegiances, confess any creeds, or salute any flags; to him, they’re so many shaky alibis for a cruel or craven humanity.

But more profoundly, and more importantly, the PI is a backstop against nihilism; a post-critical naïf whose own spartan moral code is so distilled it’s almost perfectly pure. It’s precisely in his capacity as someone who’s kicked the tires of society’s collective virtues and found them wobbly that we trust him in the driver’s seat when it comes to values. In other words, the initial, world-weary, seen-it-all shrug inevitably becomes the indignant fire that powers him to tilt at the real depravities and obscene abuses of power that invariably lie within the innermost pathways of the labyrinth of every case.

Sam Wiebe’s Dave Wakeland — the PI at the heart of four novels and one novella, each set in contemporary Vancouver — is no exception to this existential inheritance. But in his latest instalment, Sunset and Jericho (which may or may not be the end of the Wakeland series), Wiebe has raised this thematic subtext up into the letter of the text itself. In doing so, he’s written a secular religious novel; a book about a crisis of faith for a character who didn’t think he had any to begin with.

“A feeling crept over me like persevering in a fight, gaining that elusive second wind, only to expend it fruitlessly. A double exhaustion. Muhammad Ali had called that feeling ‘the closest thing to dying’.” (Page 253)

In Sunset and Jericho, Wakeland finds himself in the existentially absurd position of working for clients he holds in contempt, looking for perpetrators for whom he can’t help but feel a reluctant sympathy. Someone is taking the masters of the Vancouver universe hostage — here the mayor’s insulated goofball brother, there an overlord mega-developer with a mansion in the British Properties and another under construction on the beach in Point Grey — and demanding multimillion-dollar ransoms in the shape of donations to morally unimpeachable causes serving Vancouver’s hungriest and most vulnerable people.

Early on in the novel, we get a crash course in Wakeland’s fatalistic, cosmic minimalism in the shape of a flashback to a date with a substance-dependent ex:

Shay said[:] “I don’t even think I can explain it. What are we living for?”

She made a gesture with both hands encompassing the two of us, our watery bourbons, our uncomfortable aluminum stools. And beyond the bar, the city, the cosmos. The whole shebang.

“How is this enough for you?”

I told her I didn’t realize it was an option.

In case we missed it, Wakeland drives the point home explicitly a few lines later: “I don’t believe there is a purpose to the world. But I like people. They interest me. I find my purpose in them.” (p. 83)

Whenever Wakeland is called upon to explain his seemingly inscrutable behaviour — the enormous risks to life, limb, and reputation which he takes on to no discernible advantage of material comfort or social power — he cites a seemingly simple basic need for the truth:

“Among my many faults and quirks of personality is a stubborn need to know. It’s why I’m single, why I still live in a city that doesn’t want me. It’s why I kill friendships and houseplants with reckless abandon. I’m just that person. The one who’s not leaving without the answer […] The looking is what matters.” (p.134)

For at least about a thousand years, give or take, of Christian philosophy, Wakeland’s apparently inexplicable defining character trait would have been fairly easily identified as an especially robust capax veritatis (capacity for acquiring and understanding knowledge and truth), a subset of the capax dei (capacity for God) given to all human beings. Since God is Truth, and we were created to know God, the pursuit of truth is beatific.

But what happens to the capax veritatis when it’s uncoupled from the capax dei? Is humanism (“I like people [… ] I find my purpose in them”) enough to answer that question? If you’re thinking, ‘Hey, this is not just Dave Wakeland’s conundrum, but sorta the crisis of our entire society,’ then, my friend, you have the capax non cacas — capacity for ‘no shit.’

That’s why the inclusion of the clauses “it’s why I’m single, why I still live in a city that doesn’t want me” is so important here. Readers of the previous instalments of the Wakeland series will be wondering, ‘What happened to VPD officer Sonia Drego?’ The love of Wakeland’s life has left Vancouver for a job in Montréal — a city not only famously less expensive than Vancouver to live in, but for our paradoxical purposes here also Canada’s most assertively secular town despite (or because of) its sleeping beneath the lights of a large hilltop Cross.

Sonia’s departure hangs the possibility of Wakeland’s following suit over the novel’s whole proceedings. It explicitly separates the possibility of staying at home and the possibility of being happy.

Ultimately, this has to be part of any answer to the dilemmas of a search for truth without God. In the theistic worldview, we belong here; we’re part of a providential Creation. In an atheistic one, nobody owes us anything, least of all an explanation as to why things are so goddamn tough and inhospitable.

Faced with the growing violence of the city’s avenging kidnapping cell, Wakeland will have to sort out secular answers to a number of historically religious questions — such as whether there is ultimately a difference between justice and mercy; whether human beings can ever be used as means towards ends; whether violence is always diabolical.

But the biggest question is the perennial human one; a question that takes on new valences in the context of colonial settler land theft, renovictions, and the erasure of civic memory, but is ultimately, in some ways, permanently with us:

Am I even supposed to be here?