In both the book-within-a-book Magpie Murders and its brand new sequel, Moonflower Murders, the British mystery author Anthony Horowitz trains a magnifying glass on the process by which authors cannibalize the elements of their lives and, more significantly, the lives of other people, in order to create their works. Magpie Murders was initially recommended to me by my late Uncle Phil, who had once been surprised by the way he’d come off in one of my books — a work of non-fiction in which he’d been quoted without my having warned him. In my defence, I was 29 years old, and had no idea of the generational sensitivity of the subject matter: the aesthetic evolution of Eric Clapton.

A couple of weeks ago, a Gen-X pal sent me a sardonic text reading “I think we’ve hit peak Boomer,” and containing a link to a Vanity Fair article about Clapton and Van Morrison’s new “anti-mask anthem.” Having once touched the lives of millions with a song wrought from the obliterating tragedy of the senseless and totally unnecessary death of a loved one, it seems that Clapton, apparently no longer quite as concerned about the volume of tears in Heaven, is blithely unbothered by the prospect of reproducing such losses for anonymous strangers. Though Uncle Phil, born in 1953 and therefore demographically (if not what has come to be thought of as ideologically) classic Boomer, adored both Clapton and Morrison, there’s no chance he would have approved of the new tune. Not only because, having lost in his own just over sixty years an older brother just before the start of his own conscious life, a father while in childhood, and both a younger brother and an older sister while in his thirties, my Uncle took the sanctity of people’s lives and mortality very seriously. He also had a record of making clear when he thought his musical heroes had stepped in it, artistically. Hence the surprising line in my book, Vancouver Special, tucked into an essay about anarchism:

My Uncle Phil, once a dedicated Clapton fan, was enraged by the unplugged “Layla,” which he considered “lounge lizard music.” The laid-back, jolly serenity missed the raging, inchoate agony that had been the whole point of the original.”

When he saw the words in black-and-white, Uncle Phil thought they made him sound like a close-minded purist. Besides, he said, he had sort of come around to the unplugged version of “Layla”…

The context of the quote in an essay about anarchism was my having just prior to that sentence admitted that my favourite version of the hardcore Vancouver punk pioneers D.O.A.’s “You Won’t Stand Alone” was an acoustic version once sung by Joey Shithead on the The Mike Bullard Show. My preferences have also evolved, likely as a function of my own generational placement. Born in what most people consider to be the final year of Generation X births, 1980 — it’s a fair cut-off, as I’ve never read or seen any of the Harry Potter universe content, and got the internet in my mid-teens, when it was used for downloading erotic-for-me images of the Spice Girls that took about ten minutes to render through the dial-up — I am now 40 years old, and so rather than appreciating the toned-down versions of hard core songs, I have reason to prefer the opposite: punk rock covers of pop anthems, whose uncomplicated and accessible melodies soothe the incipient old man farting to get out of me, but performed with a pace and intensity that flatters my sense of being, still, a rebellious youngish type prepared to grab the world by the ball and/or business card.

I was 15 years old when I first heard Me First and the Gimme Gimmes revelatory cover of John Denver’s “Country Roads” (in fact it was the first version of the song I can remember hearing), but it wasn’t until recently that I discovered that these sort of cranked-up covers were something of the band’s schtick, with at least two albums full of them, & they’re terrific (there’s that punk rock sensibility again: “They’re terrific!” says Dad, lighting his pipe and carrying his fishing rod and tackle box into the mosh pit).

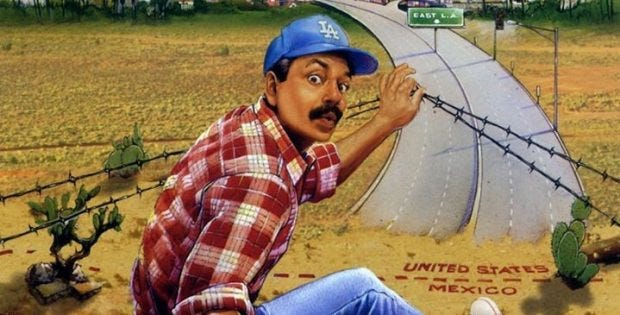

Even in their semi-ironic dress-up, the songs can be deeply touching — which is unsurprising, maybe, for tunes like Denver’s, or Elton John’s “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down On Me,” but came as a shock for me with regards to Neil Diamond’s “Coming to America.” Which is not to say that the song has never been put to effective, affective use: in the climactic scene of Cheech Marin’s Born in East L.A., for instance, Diamond’s song scores the beautiful image of two border patrol agents as they’re overwhelmed by a wave of humanity coming from the direction of Mexico, unstoppable because of their collectivity.

As I listened to the Me First cover for the first time, a few weeks ago, the poignancy came from a different place: the idea that it was utterly unimaginable that anyone would write that song, or anything close to it, today. Not to say that there aren’t people still desperate to get into the United States of America — but I suspect that this has more to do with the circumstances that they’re leaving than with the infinite 20th century optimism about the place, and the idea of the place, itself. Early on in my stand-up comedy career, I used to tell a winter-bleak and potentially, by 2021 standards, insensitive joke about a headline I had read, about an anti-immigration rally in Russia, and the multiple layers of tragedy contained within the headline itself: not only the vicious outbreak of racism, but also the very fact that there were immigrants to Russia; people whose domestic situations had reached the point where they’d said to themselves, “Let us dream of building a better tomorrow, on the gold-paved streets of… you know, Russia.”

For nearly five years, from overconfident Democrats actually hoping for Donald Trump to cinch the Republican nomination as it would ensure a slam dunk Hillary Clinton win, to George Clooney on the press daïs assuring foreign media that there would never be a President Trump, we’ve seen unconscionable levels of denial about the nature of US politics, economics, and foreign policy. But there is no analysis of American history and culture sober, unromantic, or unsentimental enough to have prepared us for just the sheer sadness of the deadly spectacle on Capitol Hill yesterday, as a mob — swelled with some of the very people least likely to ever benefit from the world that Donald Trump wants, and to whatever extent has, brought about — invaded the Capitol building in order to prevent the certification of the federal election results, leading the deaths of several people. The indelible pictures of face-painted yahoos in what appeared to be Loyal Order of Water Buffaloes hats, Confederate flag-wavers, & paranoid conspiracists mutually posing for reciprocally cordial selfies with law enforcement somehow found a way to hurt despite the fact that we’ve been numb for months.

I miss my Uncle Phil, who died a few summers ago, constantly — but I was so gratefully that he didn’t have to see what happened yesterday. Phil was broadly speaking, I think it’s fair to say, a (Pierre) Trudeau liberal (small-l deliberate); a difference from my socialist politics that felt like an unbridgeable chasm during my teens in the 1990s, and a barely perceptible distinction a few years later, when we were both a little bit more mature, and George W. Bush was the American president, followed by Stephen Harper as Canadian prime minister. We were less inclined, personally, to disagree by then; but we also found far less to disagree on (that was the main difference about the right-wing being in power in the pre-social media age: rather than obsessing on the narcissism of small differences and sectarian infighting, we “progressives” dissolved ourselves instead into a vague soup of everyone-to-the-left-of-Mussolini; a clear improvement on today’s conditions in some regards, but not without its disadvantages). But if my analysis put a premium on the conflict between classes, or between oppressed and colonized groups or nations and their oppressors, my uncle put an enormous premium on the potential for universal human decency and civility and the ability, given the proper conditions, for liberal societies to arrive at places of reasonable balance. I don’t want to suggest, even remotely, that he was naive or Pollyanna — he couldn’t stand, for instance, the exclusive sentimental fixation among so many charitable types upon children, insisting, reasonably, that “the best way to help children is to help their parents”; working for the Canada Revenue Agency, he had a philosophical understanding of the work of tax collection, and what it could do for society. When an angry dink on the phone would yell at him, predictably, that “My taxes pay your salary!,” he would tell them, “Well, I’m looking at your taxes right here, and: no, they don’t.” At his funeral, which was held in Vancouver’s Stanley Park on a busy, sunny, day, one of the speakers remarked on how much Uncle Phil loved busy parks. He was committed, at all levels, to the idea of the civic.

My last conversations with my uncle were over the phone; I called him, from the American midwest, where I was visiting my wife’s family during what were his last days at home, in the suburbs of Vancouver. I called him from Chicago, where I was looking at Picasso’s The Old Guitarist — Uncle Phil played, and he loved Picasso. But he also loved the States, where he travelled with my Aunt Lynn, whether to the austere desert beauty of the Grand Canyon, or to the streets of Manhattan where, unbelievably, they found themselves strolling a few paces behind Woody Allen and Soon-Yi Previn, and surreptitiously snapped a picture (you know, small towns!).

Last night I was texting with my cousin Steve, Phil’s son, about how much we missed being able to talk with his dad about what was going on, but how much yesterday would have broken his heart, too. My uncle’s relationship to the United States wasn’t simple: he never bought anything in US that he could get in Canada just because it was cheaper, and he once — in casual conversation but not casually at all — said that if the Americans ever tried to take over the country he’d be willing to die in the fight for it. But he did love the USA; he loved so much of the culture, and he loved the natural beauty that had come, by whatever series of indefensible historical and political processes, to be contained within it, at the expense of Indigenous nations and Mexico. And even though they often seemed to bristle, culturally, against the kind of embedded liberalism that defined civic belonging for him, he loved Americans in the abstract, too; along with more than a few particular Yanks.

My uncle’s initial problem with Eric Clapton’s unplugged version of “Layla,” as mentioned above, was that it failed to honour that the electro-psychedelic original version of the song had been a howling lamentation. I don’t know which response is the proper one to this week’s burlesque of popular uprising, and all it says about contemporary state of American nihilism; I can’t decide between howling despair and quiet, unplugged, lounge lizard resignation. But I’m glad I don’t have to see its effects on Uncle Phil’s faith in our neighbours, who spell the word without the ‘u,’ or in the general possibility of us human beings, and our abilities to share societies.

“Darling, won’t you ease my worried mind?”