A few weeks ago, my psychologist told me that my inner voice was like Ben Shapiro. She doesn’t always communicate her therapeutic counsel in these kind of Don Rickles-level existential body slams; if she did, I’m not sure I would have survived the nearly twenty years of cognitive behavioural therapy — intense courses of treatment or intermittent bouts of tune-up — that I’ve spent in her care. But as a registered massage therapist might tell you, there is bad pain, and there is healing discomfort, and I can now report that having one’s internal monologue likened to the Doogie Howser, M.D. of middlebrow political cruelty, when appropriate, falls into the latter category. It was like finding out that having a wrestler break a folding chair across one’s shoulders could be an act of chiropractic kindness.

What the doctor meant with this particular simile was that my mental narrator, like a certain right-wing podcaster, could say very stupid and untrue things with the pitch, confidence, feel, and, maybe most importantly, speed of someone saying something deeply true and insightful. The proximate cause for her analogy was a bit of COVID-era End Times despair on my part that had taken a turn for the wistful, metaphorical, and autobiographical: I was describing, for her, the growing and sometimes overpowering sense that all the good days, even such as they were, have already happened. Every night, the little robotic curator who lives inside of the iPhone puts together a melancholic slide show of vacations and birthday parties; dinners with friends, festivals with colleagues, political rallies with comrades — and each flash of memory is one that’s receding further into the distance, with what feels like diminishing likelihood of ever happening again. Slowly, over the past year, with the horizon progressively blotted out by fog, we turn our attention to the only thing we can see clearly anymore, which is what’s behind us. With nothing else to go on, we cannibalize the past. We start thumbing through the photographs and rewinding the tapes so often that we degrade even the stores of what little we had. Kierkegaard’s observation that “life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards” was already bittersweet enough, but now we squint backwards while standing still, or else falling. And to me, this all felt remarkably the way it feels to lose a parent as a child; to pore over the same scarce memories, finding them more and more fragile each time you handle them, despite your needing them always more desperately, the further you get from the love you’re trying to remember.

For illustration of the principle, we turn to Donald Duck: in 1942’s Saludos Amigos, Walt Disney’s WWII American soft power diplomatic overture to South America, Donald finds himself on Lake Titicaca (8:00), crossing an abysmal Andean chasm by rickety suspension bridge, on the back of a llama. A mishap during the crossing knocks out the wooden planks ahead of him, and Donald realizes that the only way to move ahead is to keep putting one foot in front of the other while feeding the planks that he and the llama have already crossed out in front of them. In the chaos, he begins to lose the early planks as well, and so, with fewer and fewer materials to go on, his crossing over feels less and less likely.

An English teacher once told me that a thing can’t symbolize itself, so this may be out of order, but Saludos Amigos is one of the already-crossed planks that I have fed out in front of my family’s feet so that we might continue to put one foot in front of the other during this pandemic. Talking to other parents (safely masked and appropriately spaced-out, in both senses of the phrase) at after-school pick-up, I’ve learned that our household isn’t the only one to go digging back into the vault of nostalgia-watches and cultural memories during this period of enforced prophylactic loneliness. With production bottlenecks and industry delays, not to mention an immensely vaster expanse of screen time to cover, the cultural product of a single generation — once overwhelming in its size and scope — is suddenly diminished and no longer up to the task of filling the idle hours. So we’ve gone digging into our memory banks, trying to remember which confections from our childhoods weren’t irremediably homophobic or racist or sexist or otherwise hateful, and serving them up alongside explanations for why characters don’t just look something up on the internet, or why they have to stand next to the wall when they’re on the telephone. We’ve done Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (whose experimental shrink ray was less an obstacle to the suspension of disbelief for our post-housing scarcity Vancouverite child than was the fact that all the characters had backyards) and the surprisingly-still-mostly-wonderful The Gnomemobile, which the adult me was staggered to realize was based on a book written by Industrial Workers of the World supporter and literary exposer of the meatpacking industry, Upton Sinclair. And for twenty minutes, earlier this week, we watched one of the ur-texts of my Vancouver childhood: Rainbow War, Bob Rogers’s Academy Award-nominated short film for Expo 86 about a three-way paint-based conflict between kingdoms representing each of the primary colours, which leads to the joyful discoveries of green, purple, orange, pink, the rainbow, co-existence, and cooperation.

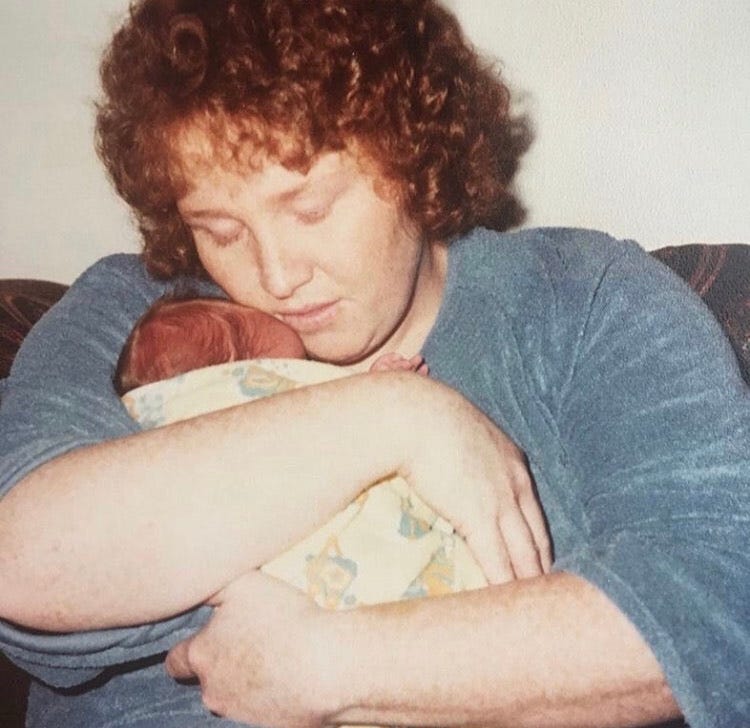

Nostalgia, in general, is a politically suspect inclination. But my nostalgia for Expo 86 specifically is perhaps especially unforgivable, given the political charge of our local instantiation of the World’s Fair. Given that it was helmed by local billionaire captain of industry Jimmy Pattison, under the authority of right-wing free market provincial and federal governments, and opposed by contemporary left-wing activists and the Downtown Eastside Residents Association as they lamented the heartless low-income hotel evictions that made way for the fair, my retrospective loyalties ought to be clear. But I was six years old at Expo 86, and not only is it the first thing I really remember about my city, and the very first truly exciting thing to have happened in my life — it was also the only good thing that happened in 1986, the year my mother was diagnosed with leukaemia; disappeared into the hospital for weeks at a time; lost all of her beautiful red hair. Sometimes, in order to visit her in the hospital, I had to wear a mask; try to cast your mind back to a time when a six-year-old in a medical mask was a jarring, aberrant sight. I wasn’t tall enough to ride Expo 86’s signature roller coaster, the Scream Machine, but believe me: inside, I was screaming.

In 1991, the year my mother died and the Soviet Union dissolved, the Marxist theorist Fredric Jameson published his book Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. At one point in its pages, he describes the “nostalgia film,” citing George Lucas’s American Graffiti as the prototype and emblematic of a late-70s fascination with the 1950s as a squandered Eden of American greatness, where even the level of rebelliousness and irreverence was just right. Today, pining for Eisenhower from the standpoint of the Ford and Carter administrations seems like quaintly short-distance longing; none of us in Joe Biden’s 2021, besides maybe David Frum, is longing for a return to 2001.

In politics or in religion, the idea that the future will be something new — that God, or society, or one working through the other, will be able to bring about something genuinely new and refreshing, rather than merely rearranging the furniture that we already have — is the basic constitution of hope. This is part of what underlies ideas like the Resurrection and End Times; so that the experience of God in Jesus of Nazareth isn’t entirely past tense, or reducible to a pile of old photos or deteriorating tapes. This is what’s behind seemingly (and even practically) utopian ideas like Jodi Dean’s sense of “the Communist Horizon” as an orientation for socialists who learn never to accommodate themselves to the present-day world of brutal hierarchy, even if that’s the one they have to master in order to do their political work. At the level of an individual or collective life, we need to have a future in mind; not at the level of proud and mulish step-by-step blueprints for the future that we try to lay onto the universe whether it fits or it doesn’t, but at the level of hope, and a belief that the story isn’t over.

My psychologist was letting me know, in deliberately unforgettable language, that my inner voice had created an elegant, confident, and spurious analogy. She was right. The idea that the political and social and medical hopelessness of the present moment makes life something like the relationship of a maternal orphan to the memories of his lost mother is one of those rare analogies that’s specious on both sides of the equation.

First of all, all our good days are not behind us. Despite the great darkness and death of the past year, the unspeakable negligence and criminal carelessness, the inequalities that exacerbated the virus and now threaten to sabotage the global process of inoculation, some of the fog seems finally to be clearing as we nose our way out of winter. The future is once again assuming a cloudy but not totally inscrutable shape: an emerging scientific consensus that we will be stuck with the virus in some form or another, but not with pandemic life; that vaccines will have to be tweaked and boosted but that they will go a very long way to keeping the great many of us safe, if we can get them to the maximum number of people. We aren’t living on leftovers. Coming out of this nightmare, all of the best elements of humanity — intelligence and curiosity; love, care, and concern; collective action and personal bravery — will be the ones that have gotten us through. There is every reason to hope, not passively but actively, that we can expand the realm of these impulses across our societies coming out of the pandemic. That will be something exciting to be around for, as will the efflorescence of creative energies, of music, drama, art, food, and more, when we can all come together safely again.

But the analogy was also wrong because however much it may feel like it, I haven’t just been getting further from my mother since she died, thirty years ago this coming month. Our conscious memories are one of the ways we inhabit the relationships with those we’ve lost, but I learned when I had my daughter that life isn’t shaped like a straight line but rather like the spiral on the back of a sea shell, taking us back around the same points from slightly different angles, at different removes: ask any mother or father who’s felt the same school day anxieties from their childhood at a parent-teacher meeting, or anyone who’s discovered that Christmas morning is even more exciting having been Santa than having waited for him. As my life keeps winding around those recurring signposts — cycles of the work, school and liturgical calendars; new phases of marriage or parenthood or citizenship or convalescence — I will keep running into my Mom, from new angles. The longer I live, I will know new things about her.

The two most terrifying ideas, somehow held simultaneously in the stilling anxiety of the present, are that nothing new is coming, and that nothing old will last. For better or for worse, we’re wrong on both counts.