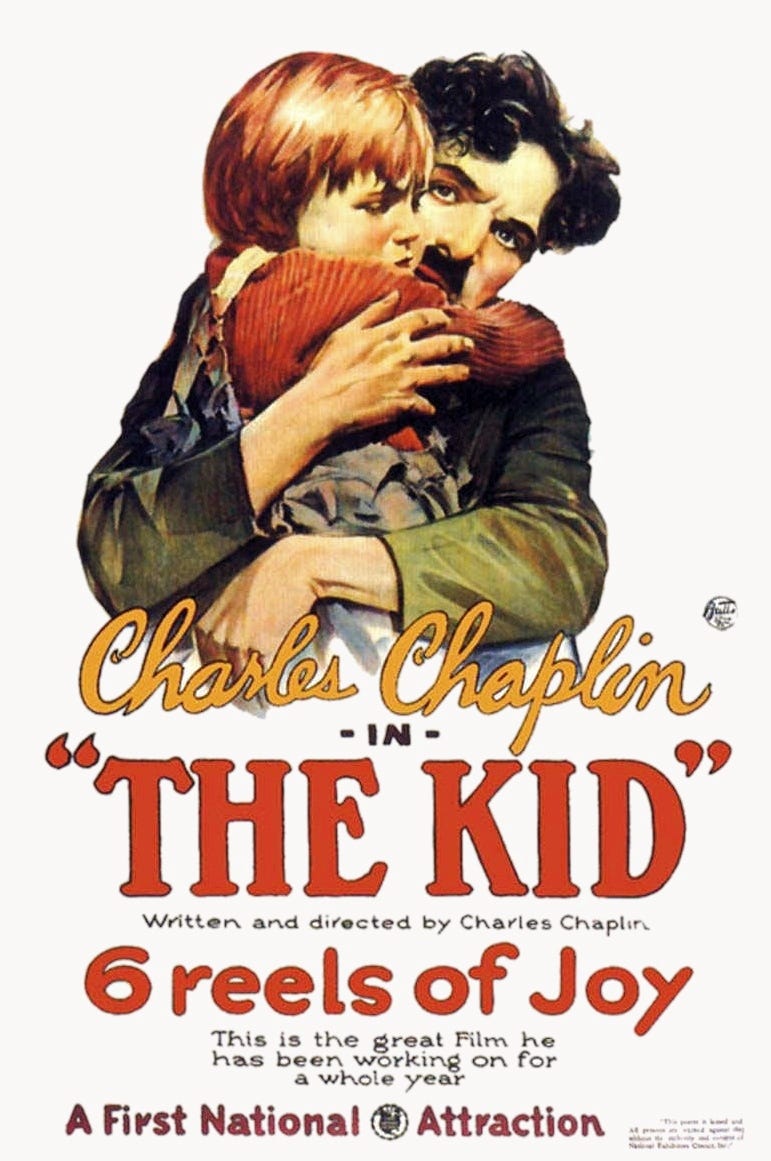

To make up for the light posting this summer, I’ll be sharing a multi-part essay on Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid, which is 100 this year, & can be watched on YouTube.

In the late spring of 2018, my four-year-old daughter Joséphine marched in her first picket line. The employees of the Hard Rock Casino in suburban Coquitlam, just outside of Vancouver, British Columbia, were striking for their very first collective agreement. Being a longtime union member and former organizer and having also myself, once, years before, performed stand-up comedy at that particular casino, I felt an especial burst of solidarity, into whose gravitational field my till-then largely apolitical — in fact if anything, given a long record of princess enthusiasm, pro-monarchical — little girl was pulled. Nevertheless, Joséphine enthusiastically donned a yellow “On Strike” placard bearing the logo of the British Columbia Government and Service Employees’ Union (BCGEU), raised her fist in the air alongside her father’s for photographic posterity, and joined the short back-and-forth walk between the two sides of the driveway into the casino.

Fairly quickly, Joséphine opted instead to ride on my shoulders, and we began to work as a team, doing our best to affect an air of innocent nonchalance as we moved tortoise-like in the path of the vehicles that were slowly nosing past the strikers. The little girl was genuinely guileless; her father was pretending to be, acting confused, struggling to choose a direction in which to walk, doing my best to play for time in order to at least frustrate the scabby gamblers, and perhaps even give them the opportunity to reconsider.

“What a great dad,” I heard from behind me, and turned expecting a partisan thumbs-up from a fellow unionist; instead, I saw the snarl of private security guard, a short woman with a very severe undercut and shrunken ponytail. “Endangering your daughter.” This was a particularly weak criticism, given the physical impossibility of the practically-parked vehicles causing us any harm. But the sneering took me back to the late nineties, walking on a solidarity picket for locked out IATSE film projectionists at a multiplex cinema on the other side of the highway, not far away. There, security guards had filmed picketers, taken their photographs, and one management stooge, observing the children playing along the line, said “They don’t look like they’re starving.” It had been a formative experience of absolutely impotent political rage (the projectionists’ union was ultimately broken), and the sense-memory now, outside of the casino, was intense.

“The only danger,” I managed, despite the bubbling flight-or-fight adrenaline screeching across my synapses, “is if somebody gives her that fucking haircut.” I only include this moment in this recollection because I’m fairly proud of it, and to establish that I really am a comedian.

Perhaps in response to this lounge-stage wit, undomesticated from inside the casino and let loose, feral, into the parking lot and against its hired goons, the security guard removed her cellphone from her pocket, aimed its camera at my face, and told me that she would be contacting child services to see what they thought of my parenting.

As I loaded Joséphine into her car seat, a police siren — as it happens, headed toward a bad accident along the highway separating the casino from the movie theatre — let loose an approaching wail, and without a moment’s hesitation, every cell in my brain compressed into a steel-hard focus on how I could escape. There was no room for logical consideration, which would have immediately discounted the idea that the tragically-coifed goon would have followed through on her empty and baseless threat; or that even if she had, that the police would have arrived immediately on the scene with sirens blaring; or of the fact that if faced with inquiring police, a white middle class professional man, articulate in English, would probably have fared pretty well; or that physical attempts to evade the police by means of motor vehicle are on the whole generally unadvisable. Such reflections, in that moment of pure psycho-biological survival, were impossible. All I felt were the same imperatives that unmistakably possess the face of Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp in the moments leading up to the climax of his 1921 feature, The Kid, as officers attempt to take from him the foundling boy who has become his son; the raging, protective love that is so human almost precisely because it isn’t, because it is animal. I love that child, it says, in a twist of facial features that manages, even from inside a silent film, to fairly scream. I will destroy any putative authority that tries to take this child away.

A few weeks later, the terror that was simply paranoiac panic in me became living nightmare for scores of families along the U.S.-Mexico border, as agents wearing at the very least moral jackboots rent parents fleeing the consequences of U.S. drug regulation, military adventures, and economic policies, from their children. Under the watchful pout of President Donald Trump — a politician whose pharaonic approach to family values has included public musings on the sexual desirability of his biological daughter — brown-skinned Spanish-speakers trying to cross a border of dubious legitimacy in order to give their families at least the possibility of safety had, in so doing, forfeited their right to those families altogether.

There has never been a time in which the commercial and political authorities of white North America stopped pulling children away from their loving parents — most especially in the mass legalized abduction of Indigenous children for cultural and, as is everyday coming more clearly to light, literal entombment at residential ‘schools,’ and in the sundering of enslaved families sold off to diverging commercial concerns. Working class families have also been hourly and daily robbed of time together by lax child labour laws or contemporary parents being forced to work double and triple shifts; the poor, proletarian, or otherwise oppressed family unit has never been sacred to capitalism. But there was something about the naked brutality of the caging of migrant children, the gratuitous cruelty of separating them from their parents, the unwillingness to indulge even in the questionable grace of hypocrisy or evasion, which drained the exigent political morality of its subtlety. We live, again, in an era of brutal, swaggering overdogs and zealously persecuted underdogs. And in this scenario, the hangdog hero of a bygone but just as unsubtly unequal age is infused with new relevance. Critics were always wrong to dismiss Chaplin’s The Kid as overly sentimental; but a century after its release, it’s clearer than ever that his masterpiece has something vital to say to those of us looking to replace the amorality and immorality of capitalism with something better.

* * *

If being my daughter comes with unfair, early responsibilities to labour solidarity and general, do-gooder activism, it also comes with some early benefits. Now aged six years old, Joséphine — a budding comedian in her own right — possesses an impressive familiarity with the Little Tramp era of the Charlie Chaplin corpus, beginning with the heavy slapstick Mutual shorts (which neither she, nor for that matter I, like as much as the later work) right up to the The Great Dictator, whose best moment by her reckoning, by far, is when a little girl, sent to see if the barber played by Chaplin is ready for his date with Hannah, a plucky Jewish ghetto heroine played by Paulette Godard, reports “Not yet — he’s polishing a bald man’s head!” This sequence was rewound and replayed in our house, conservatively, a dozen times on first viewing, with no discernible diminishment in volume or intensity of laughter. Other gags guaranteed, at present, to draw a giggling response from my junior cinéaste are in the opening sequence of The Gold Rush (1925) when the prospecting Tramp doesn’t realize he’s being followed by a black bear, or in Shoulder Arms (1918) when Charlot, enlisted as a soldier in WWI, is deep behind enemy lines, disguised as a tree.

But the first few times that we watched The Kid together, the emotionally climactic sequence in which county orphanage officials come to remove the Tramp’s adoptive son from his loving but unofficial father, proved to be too much for Joséphine, and she cried bitterly, demanding that I turn the movie off. I did my best to comfort her, though I’ve never made it through the sequence without crying myself. Having lost my own mother in childhood, I could always relate to the Kid, played by Jackie Coogan, tearfully entreating first the officials, and then the heavens, not to be separated from his parent. Now, as a father, I could also empathize with the primal defensiveness and rage of Chaplin’s character, the preconscious surge of loving anger that will see him end the sequence not only kissing his boy but chasing off the would-be abductor from the orphan asylum with the mute physicality of a junkyard guard dog. The scenes were now wrapped around me twice. I can only imagine from how many angles they must have held Chaplin, who had not only begun work on The Kid within days of the death of his infant first son, and had not only been effectively abandoned by his own father (once a successful performer) as a small child, but had also, in childhood, been forcibly separated from his mother and half-brother in the workhouses and orphanages on the cusp of the Victorian and Edwardian eras in Britain.

Chaplin had pulled on his audience’s heartstrings before, just as he had evinced a clear sympathy for the underdog and antipathy for the stuffed shirt — he was already, by the early days of WWI, as his political biographer Richard Carr would describe him, using a label developed by Steven J. Ross, “an anti-authoritarian filmmaker.” In The Vagabond(1916), a short film made for Mutual, the Tramp rescues an abused servant girl with whom he becomes infatuated, then sacrifices his own happiness so that she can pursue a painter for whom she herself, in turn, has fallen in love — before she decides, somewhat incredibly, to return and include the Tramp in her new family picture (this ending will have relevance for the denouement of The Kid); in The Immigrant, Chaplin and frequent co-star (including in The Vagabond and The Kid) Edna Purviance play a couple of steerage-class newcomers whom we root for against the bullying of immigration officials and indifferent American thugs; in A Dog’s Life (1918), Chaplin’s underdog sentimentality is displayed literally, and the pairing of the Little Tramp with an even cuter little sidekick, a formula that will lay at the heart of The Kid’s success, taken for a test drive.

But each of these antecedents was a short film, and though The Kid, at one hour, is slight by twenty-first century Hollywood standards, it was Chaplin’s first feature, and contained a depth not only of emotion and narrative but of characterization at which his earlier efforts could scarcely hint. More than simply creating an emotional affect, The Kid lays the groundwork for the moral universe in which the Tramp will exist for the next twenty years — as the avatar of what I will argue in these pages was an agnostic socialist morality that ran through his beloved silent-era feature films, including The Gold Rush (1925), The Circus (1928), City Lights (1931), Modern Times (1936), and culminating in a talkie, The Great Dictator (1940), in which Chaplin and his creation, the Tramp, would take on Hitler and fascism. The framework for all that he would do over the next twenty years, in the films that would immortalize him — endearing him not only to film historians and specialists but in an ongoing way with general audiences — is laid in The Kid, the film that promises, in the intertitle before its opening image of a “Charity Hospital” (whose appearance drew from my six-year-old almost exactly the same words as it does from Chaplin scholar Charles Maland in his 2015 audio commentary for the film: “It looks like a jail”) that it will be something different: “A picture with a smile — and, perhaps, a tear.”

Yes, or several.

* * *

The opening shot of 1919’s Sunnyside, one of Charlie Chaplin’s (justifiably) least well-received and least well-remembered early silent short films, begins tightly on the image of a cross atop a country church — and though the image feels pregnant with moral or religious or satirical portent, it comes more or less to nothing. There’s a brief feint to religious hypocrisy when the only other cross we see in the film is on the bookmark in the bible belonging to Charlie’s sadistic boss and landlord; the slightest nod to pagan pantheism, or maybe Christian panentheism, in an intertitle suggesting that the farmhand Charlie’s “church is the sky, his altar the fields” (even though for the rest of the half hour picture, he works as a hotel clerk). The closest we get to a real pay-off of the cross image is a shot of Charlie, having found one of his lost bulls, and riding it out of the church (though we don’t see either of them go in). Even here, the punchline is a little ambiguous. A send up of the parable of the lost sheep? A golden calf pun? Is he saying it’s all bullshit?

In the beginning moments of 1921’s The Kid — received not only fondly and remembered with a sort of immortality, but which would, as I will argue, usher in a new and redefining era for the already world-famous Little Tramp character and set the moral constellation he would inhabit until the the final scene of The Great Dictator almost two decades later — we’re shown a brief image of a hillside statue of Christ bearing the cross. The shot is made in connection with a young woman “whose only sin was motherhood,” and who, after briefly leaving her newborn baby in the backseat of a rich family’s automobile in the hopes of giving him a better life, is unable to retrieve him after having second thoughts, because the car has been stolen by hoodlums. Chaplin biographer Simon Louvish emphasizes that the “metaphorical still of Christ toiling uphill with the Cross” was included “even in 1971” when an elderly Chaplin re-scored and minimally re-edited the film, cutting, for instance, “a lingering scene by a church, as [the young mother] sees newlyweds come out, a stained-glass window forming a glowing halo behind her head.” When the car thieves find the baby — the film’s titular Kid — the thugs will toss him in street, where he’ll be found by the Little Tramp and, after some relatively minor and extraordinarily funny reluctance, raised by him to the age of five, by which time the child’s lost mother has become a well-remunerated stage star and the proper action of the film begins.

There is no metric on which Sunnyside does well in comparison with The Kid, and in some ways it’s unfair to contradistinguish between them. At twice the length of the former, The Kid is far more than double in substance what Sunnyside is; it’s the beginning of the story-driven film comedy which we expect of all but the very worst of funny movies today. It marks the Little Tramp’s departure from a world in which he was merely an agent of chaos and fun, a live action Bugs Bunny or Tazmanian Devil, (albeit always one with a vague affinity for the underdog), and enter into a moral key that will see him fight for boxing purses to cure the blindness of a girl who sells flowers in the street (City Lights); take a department store security job so that an orphan gamin can treat herself to all the comforts she can’t afford during the day while he patrols the shop at night (Modern Times); and fight Nazis (The Great Dictator). There is almost nothing in the kinetic, violent silent shorts he made for Keystone and Mutual to prepare us for the emotional profundity of The Kid. Short pictures such as The Vagabond, A Dog’s Life, and The Immigrant had begun to offer some clues as to the direction in which Chaplin may be heading as a filmmaker in the lead-up to his first feature, but the difference between these confections and the involved story world of The Kid are analogous to the difference between painting before and after the development of the illusion of space. As the Chaplin scholar Charles Maland explains in his 2015 audio commentary for the Criterion Blu-ray release of The Kid:

Increasingly, as he moved into feature-length films, Chaplin contrasted two moral universes: one revolving around the Tramp, and one revolving around often brutal people who obstruct his desires and relationships. Think of Black Larsen and Jack in The Gold Rush, the Ringmaster in The Circus, the Factory Owner and the Welfare Officials in Modern Times, and Hynkel in The Great Dictator. Chaplin used the callousness, heartlessness, and brutality of these characters to help generate pathos, or feeling of empathy, for the Tramp and those he’s close too.

The hillside cross shot in The Kid echoes its predecessor at the beginning of Sunnyside just long enough for us to realize how different things are this time. Because if the cross in Sunnyside comes to nothing, the cross at the beginning of The Kid offers the means by which the whole picture is to be understood. Not only because this a profoundly moral and moralistic film — a film deeply concerned with what is right, and with asking what is the right way to live, and confronting its audience with colliding, contradictory possibilities for what seems to be right, or could be right — and not only because it is a picture that is engaged, the whole way through, in a playful conversation with Christianity (whether by sending up a philanthropic do-gooder’s naive ideas about “offering the other cheek,” presenting duelling reminders between father and son to say grace before meals or prayers before bed, or finishing with a burlesque pantomime of harps-and-angel-wings Heaven). The cross is also key to understanding The Kid (the son) because ultimately it’s a trinitarian film — by which I mean that its protagonist is, like the Christian godhead, a three-in-one. When Charlie Chaplin, one of the most important working-class artists of the twentieth century — and one fascinated with the idea of multiplying himself on-screen, whether in early shorts like The Floorwalker, minor mid-career works like The Idle Class, or most famously in The Great Dictator — made the film that began the phase of his career over which he would create some of the ur-texts of democratic populist cinema and created indelible and immensely popular work that I will argue outlined a relatively consistent socialist morality, he did so with a story that featured three very different characters: his alter ego, the Little Tramp; an abandoned young boy terrified of losing his family in the face of an uncaring bureaucracy; and a rising star, beset by guilt for the past she couldn’t fix and the child she couldn’t save. And all three of them were Charlie Chaplin.

* * *

A note that I would like to make, early on, about what these posts aren’t about — particularly because we’re explicitly talking about setting the framework for one possible socialist morality, or moral universe. When it came to sex, during the phase of his life that coincided with his greatest fame and creative output, Charlie Chaplin was, essentially, a creep. He slept with adolescent girls, and didn’t treat them particularly kindly. That his unpalatable sexual history was later used against him by the most despicable forces of political reaction and hysterical anti-communist hypocrisy doesn’t make it any less gross. I would also say that anyone looking for a moral role model in a traumatized man born 130 years ago who became the world’s first movie star was always likely to come away disappointed.

It isn’t always be possible to disentangle Chaplin’s personal sexuality from his work on film — partly because they sometimes collided. The Kid was edited on the lam so that Chaplin could keep it away from the lawyers representing the minor who had filed for divorce from him on grounds of cruelty; it contains a scene in which a heavily made-up twelve-year-old actress “vamps” a grown man — four years after these scenes were filmed, Chaplin married her in real life. In a film about the imperative of protecting a five-year-old boy at all costs, it’s even more clear that we should be disturbed and repelled by the sexualization of a twelve-year-old girl. Those are distressing elements of analyzing the movie and it’s not clear to me why they should be left out of the examination — particularly as other context from Chaplin’s life will be included where appropriate.

Without turning away from that, and while including other relevant information about the historical, biographical, political, and artistic contexts of The Kid, I’m going to try to make the very important distinction that this is an essay primarily about looking at what we can see, and use, in the socialist morality outlined in the fictional universe of the most beloved working class character in international cinema history. As writers such as Louvish and Richard Carr, in his Charlie Chaplin: A Political Biography From Victorian Britain to Modern America, have made clear, Chaplin’s own politics were complicated, contradictory, and evolving over a very long life. As surveys of the artist’s own memoirs, as well as unauthorized biographies, attest, many of the details of his life are hard to pin down, though we do know the broad brushstrokes. But this world of biographical detail, mercurial and idiosyncratic opinion, or skin-crawling sexual predilection was not the universe with which the international, multilingual, largely poor and popular masses of moviegoers around the world engaged or fell indelibly in love. Put as simply as possible, their Charlie Chaplin — the one on murals in Iran and Serbia and Cuba; the one whose marquis was included in the proletarian New Deal frescoes at San Francisco’s Coit Tower — had a moustache and a bowler, and only existed in black and white. With some grey.

* * *

Chaplin’s sexual history would, infamously, leave him vulnerable to the forces of political reaction during the Red Scare in the middle of the twentieth century, making him one of the early casualties of the McCarthyite high tide in Hollywood. But his first feature film was shot, cut, and released over the course of the first Red Scare, in the wake of the Russian Revolution and worldwide labour and colonial unrest after WWI, from 1919 to 1921. Richard Carr’s detailed and probing political biography of Chaplin makes clear the star’s somewhat extraordinary capacity for muddled and contradictory political thinking — the ability to offer praise to both Henry Ford and V.I. Lenin in relatively short order — no doubt originating not only in the mixed and dynamic high modernist politics of the day but also in the vertiginous changes in Chaplin’s personal class position over the course of the first half of his life, from relative lower-middle class security in very early childhood to near-total privation in middle childhood to cultural working class adolescence and young adulthood to almost unimaginable wealth, power, and cultural cache just a few years later. Carr relates an exchange between Chaplin and Buster Keaton in 1920 — coincidental with the heart of Chaplin’s work on The Kid — in which the former tried to convince the latter of the benefits of communism: “Becoming more agitated, Chaplin banged the table and exclaimed that ‘what I want is that every child should have enough to eat, shoes on his feet, and a roof over his head!’ Reasonably enough, Keaton replied, ‘But Charlie, do you know anyone who doesn’t want that?’” Keaton’s protestations to common sense decency seem at odds with the explanation he offered, six years later, for why the hero of his classic comedy The General was fighting for the Southern slavocracy (a polity most assuredly not committed to the feeding, shoeing, or sheltering of all children): “It’s awful hard to make heroes out of the Yankees.”

If Chaplin himself was muddled, though, his Little Tramp was achieving a moral clarity that would sustain him for the next two decades, building ultimately to a climactic confrontation with no less than Adolf Hitler in The Great Dictator, and finally, in the last moments of that picture, allowing Chaplin himself to find his voice onscreen and express himself in terms of political and social principles.

But even though The Kid is a socialist picture, it is not primarily a political work but a moral one. For clarity on the distinction, we turn to the Marxist literary critic Terry Eagleton:

Like a lot of radicals since his time, Karl Marx thought on the whole that morality was just ideology. This is because he made the characteristically bourgeois mistake of confusing morality with moralism. Moralism believes that there is a set of questions known as moral questions which are quite distinct from social or political ones. It does not see that moral means exploring the texture and quality of human behaviour as richly and sensitively as you can and that you cannot do this by abstracting men and women from their social surroundings.

There are definitely political pictures that come from Chaplin later on. Monsieur Verdoux or Modern Times, are, I would argue, examples of explicitly political message movies — whereas The Kid is about that human texture to which Eagleton alludes, of how we ought to be and how we ought to be with each other. It’s also statement of a kind of working class morality at a time when a leading segment of the left in Europe and North America was moving towards a utility view of morals. In the wake of the Bolshevik victory in Russia, the Leninist-Trotskyist view of the class value of morality — that any appeal to universal or timeless morality is simply religious obfuscation, and that all moral imperative is shaped by the class struggle — was beginning to take on a certain salience on the left. And I think that the Little Tramp’s moral code makes a compelling alternative case for something more eternal.

In his book On Humour, philosopher Simon Critchley contradistinguishes between the ‘transcendental signals’ (Peter Berger’s term) sent by religion, on the one hand, and comedy, on the other. His analysis of religion wouldn’t likely pass muster with most liberation theologians, but most comedians I know would happily assent to his diagnosis of humour:

If laughter lets us see the folly of the world in order to imagine a better world in its place, then I have no objection to the religious interpretation of humour. True jokes would therefore be like shared prayers. My quibble is rather the following: that the religious worldview invites us to look away from this world to another, which, in Peter Berger’s words, ‘the limitations of the human condition are miraculously overcome.’ Humour lets us view the folly of the world by affording us a glimpse of another world by offering what Berger calls ‘a signal of transcendence.’ However, in my view, humour does not redeem us from this world but returns us to it ineluctably by showing that there is no alternative. The consolations of humour come from acknowledging that this is the only world.

In a similar vein, the cultural historian Frank Kofsky, in his study of Lenny Bruce, made the case for the comedian as a “secular moralist.” In The Kid, Chaplin sets out as an agnostic moralist, engaging in a deliberate and ironic dialogue with Christianity — arguably, along perhaps with Sikhism, the most communistic monotheism — and laying out a socialist moral universe that will govern his silent films right up until its crystallization in the famous speech delivered at the end of the Tramp’s one and only “talkie” (non-silent picture), The Great Dictator:

I’m sorry, but I don’t want to be an emperor. That’s not my business. I don’t want to rule or conquer anyone. I should like to help everyone - if possible - Jew, Gentile - black man - white. We all want to help one another. Human beings are like that. We want to live by each other’s happiness - not by each other’s misery. We don’t want to hate and despise one another. In this world there is room for everyone. And the good earth is rich and can provide for everyone. The way of life can be free and beautiful, but we have lost the way.

Greed has poisoned men’s souls, has barricaded the world with hate, has goose-stepped us into misery and bloodshed. We have developed speed, but we have shut ourselves in. Machinery that gives abundance has left us in want. Our knowledge has made us cynical. Our cleverness, hard and unkind. We think too much and feel too little. More than machinery we need humanity. More than cleverness we need kindness and gentleness. Without these qualities, life will be violent and all will be lost….

The aeroplane and the radio have brought us closer together. The very nature of these inventions cries out for the goodness in men - cries out for universal brotherhood - for the unity of us all. Even now my voice is reaching millions throughout the world - millions of despairing men, women, and little children - victims of a system that makes men torture and imprison innocent people.

To those who can hear me, I say - do not despair. The misery that is now upon us is but the passing of greed - the bitterness of men who fear the way of human progress. The hate of men will pass, and dictators die, and the power they took from the people will return to the people. And so long as men die, liberty will never perish. …..

Soldiers! don’t give yourselves to brutes - men who despise you - enslave you - who regiment your lives - tell you what to do - what to think and what to feel! Who drill you - diet you - treat you like cattle, use you as cannon fodder. Don’t give yourselves to these unnatural men - machine men with machine minds and machine hearts! You are not machines! You are not cattle! You are men! You have the love of humanity in your hearts! You don’t hate! Only the unloved hate - the unloved and the unnatural! Soldiers! Don’t fight for slavery! Fight for liberty!

In the 17th Chapter of St Luke it is written: “the Kingdom of God is within man” - not one man nor a group of men, but in all men! In you! You, the people have the power - the power to create machines. The power to create happiness! You, the people, have the power to make this life free and beautiful, to make this life a wonderful adventure.

Then - in the name of democracy - let us use that power - let us all unite. Let us fight for a new world - a decent world that will give men a chance to work - that will give youth a future and old age a security. By the promise of these things, brutes have risen to power. But they lie! They do not fulfil that promise. They never will!

Dictators free themselves but they enslave the people! Now let us fight to fulfil that promise! Let us fight to free the world - to do away with national barriers - to do away with greed, with hate and intolerance. Let us fight for a world of reason, a world where science and progress will lead to all men’s happiness. Soldiers! in the name of democracy, let us all unite!

In his excellent and illuminating commentary accompanying the Criterion edition of The Kid, Maland emphasizes the film’s theme of charity, present from the opening frames of the picture which show Purviance, the unwed mother holding her newborn baby, leaving the somewhat didactically-named “Charity Hospital.” Purviance is introduced as a character “whose sin was motherhood” — who is, in other words, without sin; even immaculately conceived if we’re to believe the intimations of the later excised halo shot — and she will, indeed, be associated with charity through the film, both as giver and receiver. Five years after losing her child, she will be reintroduced into the slums as a benevolent starlet with toys and gifts for the poverty-stricken youngsters — she will even, unbeknownst to her, bestow the present of a small toy dog to her own son (a gift that will, as it happens, later garner him the unwanted attention of a local bully). The intertitle which comes before Purviance’s gift-giving scene in the slum reads “Charity — to some a duty, to others a joy.”

The characterization seems straightforward, but takes on greater complexity and ambiguity the harder and longer one looks. Who's to say whether joyful charity is morally superior to dutiful charity? Some (admittedly penurious) schools of thought would hold that the charity which brings joy holds at least, therefore, something of the selfish about it. And if anyone in the picture has, so far, been both joyful and dutiful, it is the Little Tramp. The two scenes immediately preceding the intertitle are indicative: the Woman, to whom we have been reintroduced in the context of her newfound success, is receiving accolades and flowers in her hotel room; at one point a giant bouquet moved by no visible means of locomotion makes its way through the room — the reveal is that it is being carried by a tiny, African-American boy working as a bellhop. The Woman lets the boy go after signing for the delivery, and he allows just a moment’s frustration to pass across his face before she smirks, beckons him back, and hands him a tip, to which he responds with a broad smile and a grateful wink. The racial discomfort this patronizing moment engenders is, arguably, not merely the result of present-day attitudes projected backwards — there are reasons for thinking that Chaplin sought even originally to make this moment at least partially critical of Purviance’s character. According to Chaplin’s autobiography, at one point when it appeared that Jackie Coogan, the child actor who played the Kid, might not be available, it was suggested to him that he should instead use an African-American boy; but we also know that, owing to a strange and sentimental mixture of bathetic quasi-solidarity and liberal condescension, Chaplin never found African-Americans funny because they had “suffered too much.” It is at the very least eminently plausible that Chaplin meant for this moment to be read multifariously.

This interpretation seems especially likely when contrasted with the warmth of the scene which follows it: the Tramp and the Kid, having just finished gargantuan lunches, sit digesting with placid satisfaction when the the father pours water from his own drinking glass into the son’s bowl, so that he can wash up.

In relation to the concept of charity, the moment calls to mind Barbara Ehrenreich’s observation that “the real philanthropists in our society are the people who work for less than they can actually live on. Because they are giving — of their time, and of their energy, and their talents — all the time.”

In this reading, Maland’s framing of The Kid as a film about charity seems too restrictive — it is, rather, more rightly seen as a film about love, as in the injunction which the Woman affixes to her baby by the pin that will prick the Tramp’s finger before he reads it: Please Love and Care for This Orphan Child. This is language reminiscent of the prophet Isaiah’s: “learn to do good; seek justice, rescue the oppressed, defend the orphan, plead for the widow.” It is this prophetic care for the orphan (and the poor, and oppressed) that the liberation theologian José Miguez Bonino identified as being not only demanded by God, but literally constituting the human knowledge of God. It is a radical idea bearing repeating: that there is no way for human beings to contemplate God outside of the acts of caring love for others. As Eagleton explains, “[l]ove in the Judaeo-Christian tradition means acting in certain material ways, not feeling a warm glow in your heart […] Love is a notoriously obscure, complicated affair, and moral language is a way of trying to get what counts as love into sharper focus.” There are no better human conceptions than these for understanding the relationships between the trinity of characters — each of them biographical Chaplin-avatars to a certain extent, but transcending his personal story.

Over the course of The Kid, Chaplin will — in non-religious language, but with a series of cues that will keep religion on the horizons of the film’s meaning, so that we’re always aware of the size of canvas that he’s painting on — take the Tramp, the Kid, and the Woman through a series of circumstances, gags, and jeopardies which will offer genuine insights of non-utilitarian, non-revolutionary (by which I mean, unlike the Leninist-Trotskyist moral model, not conditioned by the immediate exigencies of a revolutionary situation) socialist morality in relation to perennial human themes.

Over the course of this essay, which I’ll post in in parts, I’ll look at the film in its context — in world and political history, in the context of film as an emerging art form, and with regard to the relevant points of Chaplin’s biography — and explore what it has to say about some of these themes, and how their presentation in The Kid anticipates their expansion across the following two decades of the Little Tramp’s silent film universe. On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of The Kid’s theatrical release, I’ll ask what the continued relevance might be of the moral universe of which it marked the Big Bang, and look at what prospects there are for an engaged, moral, socialist comedy in the twenty-first century — whether it’s still possible to be all four, and whether anybody really wants it to be.

I will strive, at all times, to make the experience more joy, less duty.

Please consider subscribing for full access to future installments of this essay & other writing!