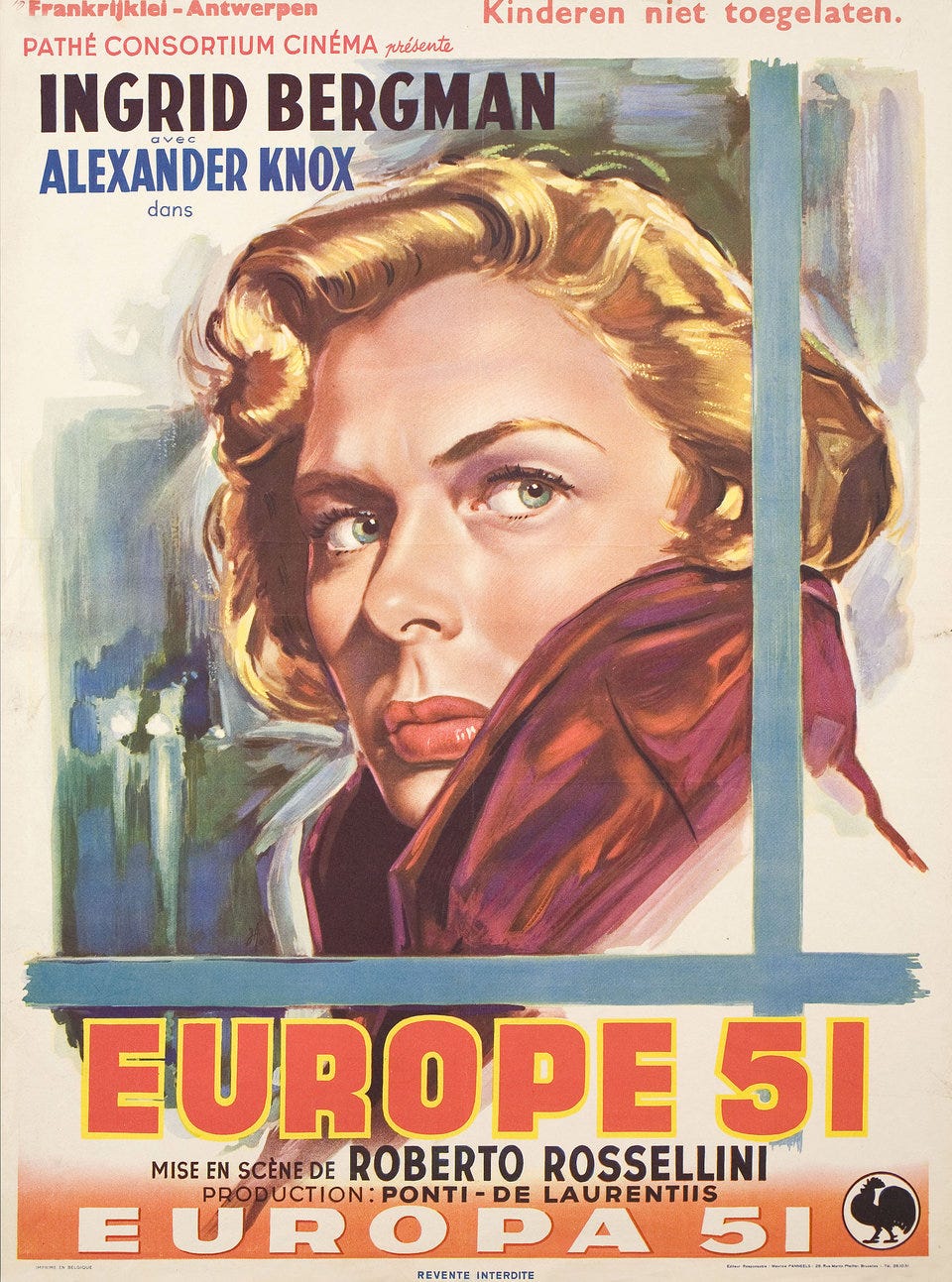

To describe the mid-twentieth century international film star Ingrid Bergman as ‘iconic’ would, under most circumstances, be to use the domesticated language of celebrity culture hyperbole — but in reference to her performance in 1952’s Europe ’51, the term reverts to something of its original, sacramental meaning. One of her collaborations with romantic partner Roberto Rossellini, the film is explicitly paired by its contemporary curators with the director’s preceding film about arguably the most spiritually and ecclesiastically impactful deacon in church history, Saint Francis of Assisi: “[t]he intense, often overlooked EUROPE ’51 was, according to Rossellini, a retelling of his own THE FLOWERS OF ST. FRANCIS from a female perspective.”

Seen in the retrospective light cast by Europe ’51 and its portrayal of life-giving, kenotic diakonia in the figure of Irene — the story’s protagonist, played by Bergman — the gentle calm and meditative peacefulness of The Flowers of St. Francis (1950) makes new sense against the violence and despair which preceded it in Rossellini’s post-WWII output. In 1948, the director had released the final and bleakest instalment of what has come to be known as his “post-war trilogy” (Rome: Open City; Paisan; and finally Germany: Year Zero), filmed in the rubble of a flattened and occupied Berlin, and culminating in the most hopeless of nightmares: juvenile suicide. Then almost unfathomably, two years later, came the nearly unspeakable beauty of The Flowers of St. Francis, a perhaps appropriately beatific adaptation of the late-medieval collection of Franciscan history, legends, and lore, made with the collaboration of a professed Franciscan, as well as one Dominican, friar. Despite the raging and vastly destructive warfare of Francis’s time, either between Italian city-states (violence in which the pre-conversion Francis had been caught up, leading to an extended and traumatic imprisonment), or in the Crusades (to whose Egyptian front lines the post-conversion Francis famously despatched himself in order to convert the Muslims, leading instead to a celebrated encounter with Sultan al-Malik al-Kamil, now regarded, perhaps legendarily, as an early prototype for respectful inter-religious dialogue), this connection with war-ravaged mid-twentieth century Europe is left unexplored in the picture; the one sequence which deals with a warlord is played largely for laughs.

The film is, instead, a soft and invitational one, portraying Francis as an icon of Jesus the Christ, sending out his disciples in every direction at the picture’s end in the manner instructed by the Gospel of St. Matthew. This parallel-drawing between the life of Francis and the life of Jesus is also true to the film’s source material, as in this passage from The Little Flowers on Francis’s Lenten fast at Perugia: “In many ways, as a true servant of Jesus Christ, St. Francis was given to the world as Christ himself was: for its salvation. God’s will was accomplished through Francis, as we saw in the lives of the twelve companions, the mysteries of the stigmata, and in the continuous fasting of holy Lent that Francis kept in the following manner.” In fact, in his introduction to his edition of The Little Flowers, the scholar Jon M. Sweeney points out that the faction of Franciscans originally responsible for the book were “comparing their revered founder to Jesus in ways that understandably made more mainstream Franciscans (as well as a few popes) uncomfortable.”

The seeming disjuncture, however, between Germany: Year Zero and The Flowers of St. Francis is erased by Rossellini’s feminine recapitulation of Franciscan themes in an explicitly contemporary context in Europe ‘51. And rather than providing an icon of Christ through literary allusion or aesthetic rhyming, we have, instead, in the words of Ormonde Plater, a “distinct symbo[l] of Christ the servant.” Bergman plays Irene, the wife of a wealthy representative of American industrial interests in Italy, who buries her trauma from the British air raids in the incessant niceties of bourgeois socialite life — until her 12-year-old son, with whom she cowered during the bombings, throws himself down a stairwell, dying shortly afterwards. Initially paralyzed by despair, Irene is drawn out of her bourgeois social enclosure by her husband’s Communist cousin, Andrea, a man driven as much by selfless principle as by haughty condescension, and also, possibly, an attraction to his cousin’s wife. Andrea introduces Irene to a working class family whose son’s life her money can save with an otherwise unattainable operation, and she comes quickly to realize that the only salvation, for her or for others, lies in agape. In an exchange with the Marxist Andrea, Irene — whose name, invoking peace, also echoes Irenaeus, thus associating her with martyrdom, apostolicity, and the elimination of heresy — makes it clear that, without ignoring the immediate physical needs of those around her, she is operating at dimensions of redemption more profound than the exclusively material plane to which his project is restricted:

Andrea: We would have a paradise — here on earth. Real, material. Willed and made by man.

Irene: Perhaps. But if only everyone would understand that the problem is much deeper than that. More spiritual. Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. Only that will bring us close. Closer to one another as equals. Humble in the same way — for only with love will we find salvation together. I want to thank you Andrea. You’ve opened my eyes, in spite of your ideas. I know now that all my life’s been a mistake. If God would help me! […] I want to make sure that [my son] Michel knows how great my love for everyone is. It’s part of my love for him.

Drawn in to the geography of working class life in her city, Irene meets a young mother raising six children alone; she finds her a job in a factory, then works one of her shifts so that the woman doesn’t have to break a date with a young man. Irene moves into the apartment of a sex worker, dying prematurely, who lives in the building of the boy whose operation she paid for; the woman is shunned by her neighbours, but Irene brings her first a doctor and then, after the fatal prognosis and last rites have been delivered, spoon feeds the woman her last meals, and bears solemn witness to her final moments. The Flowers of St. Francis is the deacon saint in stained glass; Europe ’51 is Saint Francis of Assisi in stained washcloth and stained apron. In tracing the story of a renunciation of privilege in favour of diakonia, and emptying of personal wealth and comfort in prophetic ministry to the sick, the naked, the hungry, the thirsty, the imprisoned, “the least of these” (Matt. 24: 42-45), it follows the biographical arcs of the founding saints of the Franciscan way, both Francis and Saint Clare, intimately. And as we prepare to move into the aftermath of the greatest global trauma since WWII, at a time of deep malaise and unrest, this extended meditation on Franciscan spirituality and its responses to human brokenness in the face of mass devastation are deeply instructive.

In the comings months, years, and decades, nothing will be more urgent than the loving care and recuperation of the creation that sustains us, with concomitant respect for the integrity of the embodied lives of other creatures, human and otherwise, with whom we are related and entangled; the nurturing of just peace, mutual respect, and friendship with those we’ve been taught to imagine as enemies; the renunciation of hoarded wealth and its liquidation to slake the thirst of the poor and exploited; the tending of the sick, whether in body or in mind. While it would be delusion to imagine that Francis’s medieval circumstances could speak directly to ours without any remainder, we’d equally have to strain ourselves not to hear the resonances between them. In Europe ‘51, Bergman and Rossellini reimagined Francis for the darkness of postwar Europe; as we begin to make the first tentative steps towards postpandemic life, maybe another wave of saintly recasting is due.