When Salman Rushdie finally wrote his memoir of the years he spent in hiding from the Iranian government’s bounty on his head for the putative blasphemy in his novel The Satanic Verses, he wrote it in the third person and titled it Joseph Anton, after his police code name during those times. In the pages of the book itself, Rushdie tells the story of the pseudonym’s composition — a piece of work that he worried over until he came up with just the right combination of sound and significance: the given names of Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov.

How this story comes across to you probably depends a lot on what you think of literary or creative endeavour in the first place. A hunted man straining for the perfect combination of modern literary namesakes to be barked indifferently over walkie-talkies by the cops trying to make sure he doesn’t get killed might seem like the height of fussy pomposity — but it’s really more like a death row prisoner’s turning the wall of his cell into a mural; a stubborn, defiant insistence on the right to assert and insert signification, significance, and creativity into even the most dehumanized circumstances.

The memoir is full of prosaic details about going into hiding, for example what kind of cars can be made bullet-proof, or the dangers of weight gain from a newly sedentary and ultra-depressed lifestyle — as well as who paid for Rushdie’s protection, which was, mostly, him. Having written Midnight’s Children, a worldwide literary sensation, as well as other top sellers by that juncture in his career, Rushdie was pretty flush. But at one point, he turned to the police officers guarding him and asked, “What if I’d been poet and this had happened?” He basically gets a shrug in response. Good thing you aren’t a poet.

No, Rushdie is a writer of prose — and while he is best loved and most widely purchased as an author of literary prose fiction, postmodern and occasionally magical realist novels and sometimes short stories or children’s literature, I’ve always best loved him as an essayist. At some point in my twenties, I lucked upon a hardcover first edition of Rushdie’s 70-essay collection from Granta, Imaginary Homelands, for which it appears I paid $14.95. The story of Imaginary Homelands is enfolded into the story of Joseph Anton — most specifically, how it came to include its notorious concluding essay, “Why I Have Embraced Islam,” which features only in the first edition.

“Why I Have Embraced Islam” is a very strange piece without the context provided by the memoir; it’s baffling without the knowledge that it was written as a sop to Rushdie’s more moderate enemies at the bleakest nadir of his hiding, in a desperate bid to end his ordeal. In Joseph Anton Rushdie, a lifelong atheist, expresses his wrenching shame over the piece, and his relief not only at its expurgation from future editions of the book but also of his abandonment of the dead-end strategy of rapprochement with those who would ban him (and worse). As a writer myself who has written non-coerced, genuine first-person non-fiction prose about the return to faith in adulthood, Rushdie’s essay reads excruciatingly like a statement read at gunpoint, and the experience he describes is not only devastating to read but also outlines, I think it’s fair to say, the furthest possible thing from a route to the sublime sacred in any vernacular or tradition. I’d go further, in fact: Rushdie’s dignified humanism charts a more appealing hallowing of being than any fundamentalism I’ve encountered.

Joseph Anton is a massive book — I listened to it, in fact, on audiobook CD’s bought from the Vancouver Public Library; the text was read by the same (it has to be said) courageous actor who read The Satanic Verses, and at 27 hours, with my only CD-player being in the dashboard of the 2013 Corolla, it took me all summer to get through it.

The two main thoughts I kept having as I listened were the following:

First, that Rushdie was in some ways the last intellectual of the 20th century and the first intellectual of the 21st.

The years of his life that lead up into the time of the bounty on his head, though built on the success of postmodern novels and postcolonial fluidity, were in most ways decidedly modern. He was part of the generation of baby boomer bad boys who could flip around the furniture inside of an Establishment that was still very clearly standing. He worked as an advertising creative and then became a successful literary author, flying around the world to important literary festivals, meeting other important writers. Middle-class people were expected to know, or at least know of, his work, just as they were meant to know about all the important novels that came out that season, of which there were a manageable number, nearly all from within the Anglo-American world (today, a screenwriter hiding from death threats and footing the bill for expensive security might ask her cop handlers, “What if I’d been a novelist and this had happened?”). Left-liberals generally liked him, the right-wing racist British press hated him — and those affinities and distastes made a weird kind of intuitive sense within what everybody knew about what politics and society and people were like.

Coming out of the years of hiding, Rushdie’s life was now more postmodern than his work. He appeared in Bridget Jones’s Diary, as himself. He married a shimmeringly beautiful model and reality TV cooking show host. He had dinner at Tony Blair’s house, and when he was told that the children had not yet named a large teddy bear they’d been given, suggested the possibility of “Tony Bear” to stony silence. He now had enemies on the left, who considered that his apparent blasphemy had heaped scorn onto Britain (and the globe’s) underdogs, and cheerleaders on the right, who saw his case as a handy referent for obscurant Islamist brutality during the War on Terror. Like his former-lefty friend, Christopher Hitchens, he flirted with the possibility of NATO and US military power as tools for building a better world (a trend brought back in fashion recently by reflexive anti-Putin and anti-Trump instincts). He had essentially experienced the prototype of the online swarming, with its attendant floods of error and slander, vitriol and bad actors, nearly 20 years before Twitter was invented.

The other, related thought I kept having was much more depressing: that if the “Rushdie Affair” were to happen today, many people I know (and love) would be likely to say, “Well, it’s complicated”; or, more probably, post memes and Twitter screenshots to that effect.

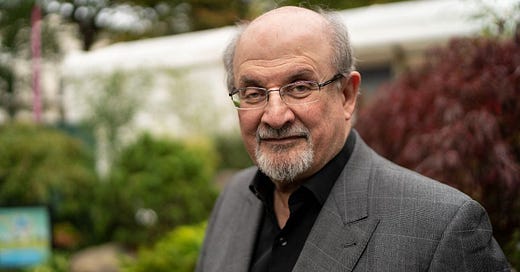

I’m writing this as Rushdie receives surgery for multiple stab wounds in and around the neck after being attacked at a literary event. The only thing I know about the attacker is that he was wearing a mask. We’ll learn more in the hours and weeks to come.

That all this comes in the wake of a brutal assault on the Gaza Strip by the Israeli military calls to mind Rushdie’s old friend, and uncompromising defender, the late Edward Said. As a young man I remember reading about Said having arguments with Palestinian comrades in the West Bank on Rushdie’s behalf — it was a model I found inspiring then, and nothing about it has dimmed.

Because of his long commitment to the freedom, sovereignty, and liberation of West Asia and North Africa; because of his long championing of the dignity and worth of the intellectual and cultural traditions of the Islamic world, especially with regards to its objectification by European imperialism; because of his long and spotless record of holding sacred and dear the value of Muslim life, Said, a Palestinian-American non-practicing Christian (Anglican!), had the moral authority to call the bounty on Rushdie’s head precisely what it was: a cynical, indefensible outrage against free expression, to be opposed without throat-clearing or equivocation.

In a context where the decades-long hammering and years-long economic strangulation of Gaza evoke not a scintilla of the outpouring Ukraine (rightly) received within hours of being invaded by Russia, it not only becomes difficult to defend liberal-democratic norms whose whole essence is their consistency — but outrages like the Rushdie book-burnings, and threats, and bounties, and now quite likely this attack, can be offered by some bad actors as a sick, cathartic substitute for a justice that seems as though it’s never going to come.

This isn’t What Aboutism, and it’s not making everything about everything else. Whatever your politics are, or if you’ve never had an opinion on anything, the vicious stabbing of an author deserves your opposition on its face. But Said, whose presence runs through the pages of Joseph Anton, long ago set the tone for how to do it, not only most consistently, and most humanely, but most effectively.

Solidarity with Salman Rushdie.