The first time readers met Ian Rankin’s Edinburgh detective John Rebus, in 1987’s Knots & Crosses, they were supposed to suspect — until fairly late into the novel — that he might in fact have been the very serial killer that he was investigating. (Strictly speaking, that sentence probably should have come with a spoiler alert, but in fairness, 1) the book is 35 years old and 2) it wouldn’t take a hardscrabble Scottish inspector to figure out that a character who’s so far spawned another few dozen novels and short story collections likely didn’t kill several children in the first book.) In the opening pages of his most recent outing, A Heart Full of Headstones, Rankin has Rebus in court — as a defendant. Rebus’s trial takes place under Scotland’s ongoing COVID protocols, with detail inspired by Rankin’s real life son’s jury duty experience in the time of coronavirus: the jury aren’t in the courtroom but sit off-site in a movie theatre, watching the proceedings on closed circuit television. Rebus is on trial and on camera.

The jury aren’t just a jury, then, but an audience; just as we, the readers, are. And as one audience sits passively consuming Rebus’s story for judgement, the other sits in judgement on itself for passively consuming Rebus’s stories.

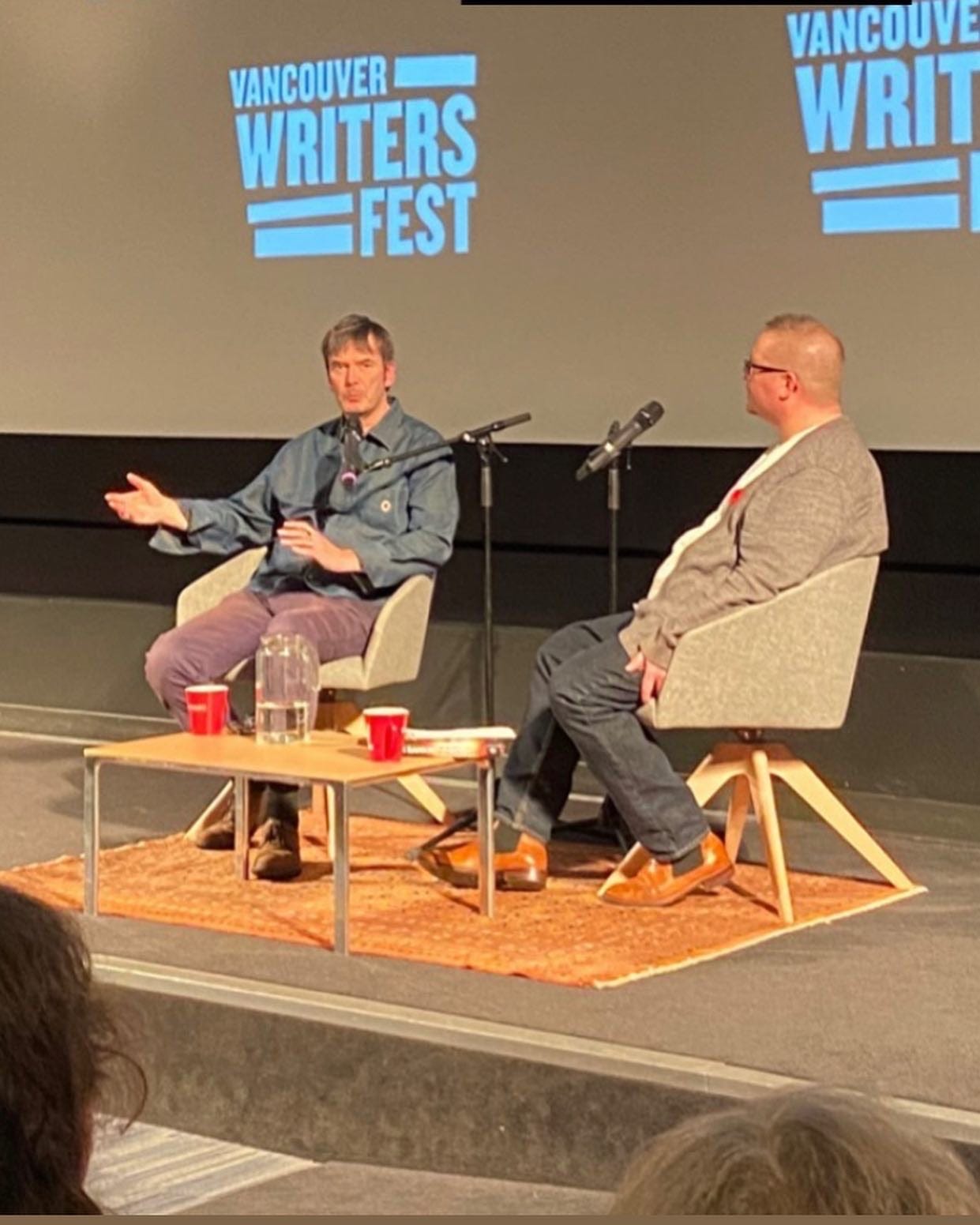

When I spoke to Rankin last week in front of a Vancouver Writers’ Festival audience at SFU Woodwards in the Downtown Eastside, he explained the significance of Robert Louis Stevenson in forming his picture of literary, and even physical, Edinburgh. He reiterated that Knots & Crosses had been meant as a 1980s retelling of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (though, to his charming irritation, it hadn’t been read as such by anybody else). But if Knots & Crosses asked if Rebus might be Hyde without knowing it, A Heart Full of Headstones asks if maybe Rebus was Hyde the whole time we thought he was being Jekyll.

The action in Headstones turns on two plotlines rooted in Rebus’s complicated, intimate enmity with crime boss Big Ger Cafferty — who, like Rebus, is now in his relative dotage, the two men both physically reduced from their primes, with Cafferty bound to a wheelchair and Rebus beset with COPD. Cafferty has hired the now-retired Rebus for a bit of private eye work, turning up an old underling once thought dead (at Cafferty’s hands) but recently spotted alive and kicking. In the meantime, Rebus’s friend and former protégé Siobhan Clarke is investigating first a uniformed police officer, Francis Haggard, accused of spousal abuse, and then Haggard’s murder after he threatens to turn whistleblower as a line of defence.

Haggard claims that his abusive temper and outbursts stem from PTSD caused by his service at a rogue police station, Tynecastle, whose culture of bullying, violence, misogyny, brutality, and corruption had essentially left him a monster. The emeritus ringleader at Tynecastle is Rebus’s also-retired friend, Sergeant Alan Fleck — for whom Rebus once facilitated a meeting with Big Ger Cafferty.

Headstones is a post-pandemic novel, full of face-masks and quarantines (Siobhan only gets the Haggard case because a colleague is in isolation after testing positive; he’s the novel’s only well-rested character, the envy of every hale and healthy detective on the force). Nearly each character here is driven by one or both of the overriding fears of 2020: that things will never be the same, and that nothing’s ever going to change. Cafferty and Fleck are reduced to taking in the city by telescope and early morning risings from bladder weakness, respectively, but neither is willing to let go of his power from the Good Old Days. Fast-rising Inspector Malcolm Fox and Cafferty’s looming lickspittle henchman, Andrew, are unambiguous votes in favour of the future, but with their optimism wed more to an unseemly personal ambition rather than actual hope.

The twin moral centres of the story are each more tentative in their partisanship for past or future. As the investigation of Alan Fleck and the Tynecastle cops threatens to take her friend Rebus down with it, Siobhan is initially torn in her loyalties. But her meetings with Haggard’s battered widow, as well as her hearing the harrowing story of a female officer once stationed at Tynecastle, keep her committed to pursuing desperately needed evolution. For his part, Rebus — described by Rankin as “a small-c conservative” — begins the novel’s action in a mode of unreconstructed nostalgia. “Music’s moved on,” Siobhan says to him at one point, over breakfast.

‘Got worse, you mean, like everything else.’ He looked at Clarke’s plate. ‘Apart from bacon rolls. You can trust a bacon roll.’

But the longer he has to consider his history with Alan Fleck and the police at Tynecastle, the more honest and incisive Rebus’s self-examination becomes. And if Rebus has been a dirty cop this whole time, then where does that leave his millions of fans — not at Tynecastle, but under reading lamps around the world?

In the film, television, and books of the 1970s and, especially, 1980s, the maverick, rule-breaking police officer was more than simply a stock character; he was heroic archetype. In a time when bureaucracy was identified as the great evil stalking North Atlantic industrial societies, the cop who broke the rules was not only played for vicarious thrill and adventure — he was the only fictional cop we knew we could trust, precisely because he broke the rules. This tendency is usually associated with right-wing backlash, and rightly so; but it was not exclusively a conservative phenomenon. Sidney Lumet’s Serpico, for instance, offered Al Pacino as a magnetically countercultural cop against an impossibly corrupt police hierarchy.

Conventional wisdom has shifted, though, and the case against rule-breaking cops has found a greater amplification than perhaps it ever has in the mainstream conversations in Western countries. So where does that leave results-oriented rogues like John Rebus? And does his moral culpability extend to the readers who lived through him, thrilling to his exploits?

In the hands of a less interesting or more cynical writer, A Heart Full of Headstones could have been a simple exercise in weathervane following. But Rankin’s characters are too fully human for any panicked 180-degree rebranding. It helps that he’s willing to do what not many writers are anymore: to leave moral judgments in the hands of his readers. It’s never confirmed, for instance, one way or the other, whether Haggard’s invocation of PTSD as a line of defence was cunning ploy or cri de coeur; reasonable readers will differ. And this is where Headstones as pandemic novel works best in service of its theme.

This is a novel about contagion; about the way that disease spreads literally and corruption spreads metaphorically by contact or association. For both kinds of contagion, sometimes quarantine and cordon sanitaire are necessary, life-saving measures. But in the long run, the idea that we can deal with illness or corruption simply by lopping them off or blocking them out is a self-destructive fantasy. The Tynecastle police station is run like a settler fort or military outpost; time and again, throughout the novel, characters in well-defended physical structures learn too late that the real threat to them is already in the building.

Part of Haggard’s bullying initiation at Tynecastle relates to his given name, Francis; the mostly-Protestant officers call him ‘Saint Francis,’ a sectarian dig at his being Roman Catholic. But Saint Francis of Assisi is a useful key for the text. In a novel ridden with warped father figures — Alan Fleck, Big Ger Cafferty, Rebus himself — Saint Francis is a figure who famously renounced his earthly father in favour of his heavenly one. But more importantly, as Saint Francis grew in holiness, his one-time revulsion at leprosy grew into a love and devotion to lepers. His commitment to nurturing and caring for those with the disease was such that it may have been the reason his own life was cut so short. It’s also what brought him either immortality or eternal life, depending on your metaphysical orientation to history.

When I asked Rankin about the religious imagery and themes that had been so prominent in the early Rebus writing, he explained the way that Rebus’s spiritual explorations had mirrored his, Rankin’s, own needs, and then waned accordingly. But A Heart Full of Headstones is about the very possibilities of hope and redemption, and when the cases you’re pursuing are that big, a good investigator knows that nothing’s off the table.

Great review. I so enjoyed your conversation with Ian Rankin. Keep writing

Wendy Williams