Guest post: Comedy Without Cocaine

An excerpt from Alex Wood's new memoir from my literary humour imprint Robin's Egg Books

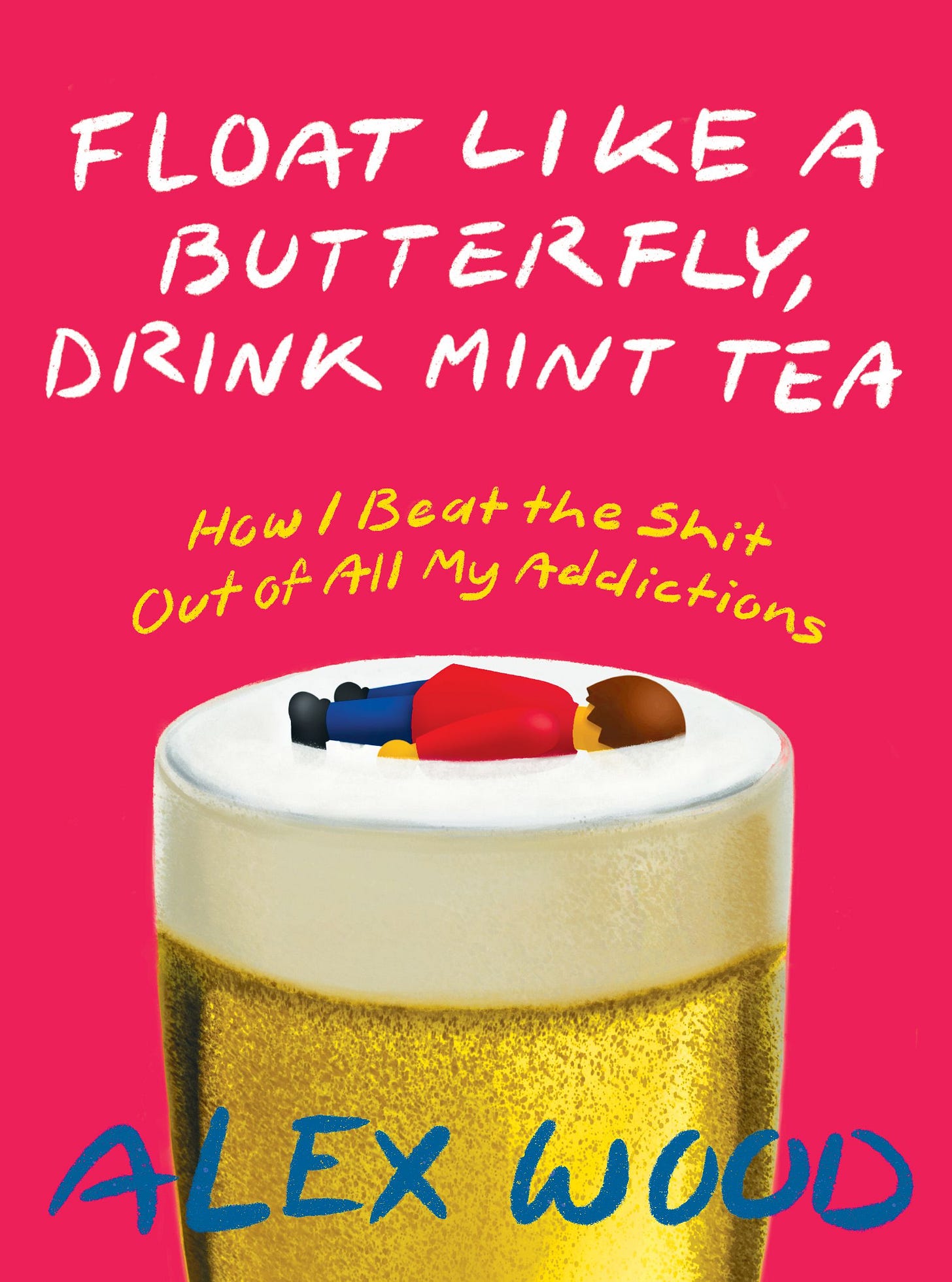

Over the years I have been lucky enough to publish a few of my own books with Vancouver’s legendary Arsenal Pulp Press, & a little while ago this led to the opportunity of curating & editing an imprint of literary humour books by other authors. I am inordinately proud of these books, & the most recent, published just a few weeks ago, is no exception. Somehow still hilarious, it is the deeply harrowing story of Ontario comedian Alex Wood’s struggle with multiple, overlapping, very serious addictions, & his journey to understand & conquer them all. It’s a love letter to comedy & to life itself, it was an honour to get to work on, & you can get your own copy here or anywhere fine books are sold.

It was the middle of October by the time I finally took a few days off coke, and it wasn’t by choice. Wafik was on the road, my dealer cut me off because I owed him too much money, and I was flat broke. I thought I had contracted an illness because I was completely brain dead, sweating, shaking with chills, and constantly feeling like I was going to throw up. I was dope sick from withdrawal, but I thought I was just under the weather. That’s how deep denial can run when you’re in the throes of addiction.

I’ve been going really hard on the booze and coke lately. I suddenly stop and feel physically sicker than I ever have. Holy fuck. It’s that swine flu (or as we call it now, the good ol’ days).

It was a real bad case of the Mondays. I wasn’t even able to sleep until early Tuesday morning. When I woke up, looked at my phone, and saw it was three p.m., I thought, Wow, great—I actually slept seven hours. Then I saw something beside the time that confused me. It was the word Wednesday. It took me five minutes to realize that I’d just slept for thirty-one hours.

I had a voice mail from the owner of the Absolute Comedy club in Ottawa. Jason spoke like a cocaine addict, even though he didn’t do cocaine. Hundreds of words in a single minute. He was the first person to give me paid shows, spots longer than six minutes, and gigs in other cities. I was his Golden Boy. The only criticism he had for me was that I smoked too much weed. He hated cocaine, and I knew he would be furious if he found out how much I was doing in his bathroom before I would go on his stage to perform. I checked the message and it was his familiar ranting.

I promise you, this voice mail was somehow only four seconds long: “It’s fucking two in the afternoon and you’re still asleep, aren’t you? Holy fuck, you lazy pothead, get up. I’m trying to give you money. When I was your age I never would have missed a call from a booker and cellphones weren’t even a thing yet. You gotta be more professional. I need you to host the club tonight, but if you don’t get back to me soon, I’ll have to call someone else.”

Immediately, I called him back. After all, I needed that seventy five dollars for cocaine.

When I got to the club I didn’t have that spark in my heart to perform. It may not sound like much, but that was the first time that had ever happened to me. I wasn’t at the club because it’s where I always thought I belonged. I wasn’t there because making people laugh was the best high I ever got. I was there to make drug money.

About twenty minutes before the show I decided to try to mimic the pre-show cocaine high that I was now in full need of before going onstage. I chugged two cups of coffee and a beer, I smoked a joint and two cigarettes, and I downed a shot before grabbing another beer to take with me.

The announcer’s voice said, “And now your hilarious host and emcee ...” and I started my walk to the stage with total emptiness in my heart. I put my half-empty pint glass on the stool and grabbed the mic out of the stand like I had done hundreds of times before. “How you guys feeling tonight?”

The crowd roared with excitement.

And that’s when I felt it. Something was seriously wrong. I was going to pass out.

“Your headliner is in the back of the room. Let him hear it.” The crowd roared again.

I was about to die right in front of these people. My heart was barely beating. I was dizzy. Sweat was dripping down my spine, and every muscle in my body was tensing up.

“I’ll tell you guys what’s going on with me—” That was just a line I would say to transition to material when I hosted. I never told anyone what was going on with me, and I wasn’t about to start with these people.

“I recently—” I couldn’t finish my sentence. Oh, fuck. What is happening? I paused.

“I recently joined a gym—” was the last thing I said before I turned to the half-empty pint glass and vomited into it. It over flowed the cup and ran down the stool and onto the stage. This was less than one minute into the show. If you haven’t ever been to see stand-up comedy live, this isn’t how we typically like to start a show. I’ve never heard a crowd that silent. It was “Is he really doing an impression of that accent right now?” silent. I’m talking “Is she really doing another ukulele song about the patriarchy?” silent.

Nick, the doorman, ran a garbage can to the stage. I wasn’t even done with my hand signal to let him know that the garbage can wouldn’t be necessary before I started vomiting violently into it.

The crowd’s eerie silence was broken by one guy yelling out, “What the fuck?” before he was joined by horrified gasps and screams. After I was done throwing up, the crowd went silent again. No one, least of all me, knew what they were watching. People were checking their ticket stubs like, “What kind of performance art is this?”

Nick asked me if I was going to still do the show. The microphone picked up his question and the entire crowd leaned forward in antic ipation. I said yes. Nick and I always knew what the other was think ing when it came to comedy. He tossed me a softball.

“Do you need anything?”

“Maybe a ginger ale. My tummy hurts.”

It’s still, to this day, one of the biggest laughs I’ve ever gotten, onstage or off.

I told the audience that I had been fighting the flu and hadn’t eaten in days, which was as close to the truth as I was telling people at that time. I then did an impression of what had just happened with a sports announcer’s voice calling the action. For the next twenty minutes, people were stomping on the floor they were laughing so hard. The kitchen staff ran upstairs because they said they thought the roof was going to cave in. During the first act, Nick and I came up with another bit. I went onstage wearing a garbage bag like a poncho. I didn’t even say anything, just stood there, deadpanning. Another laugh so big it actually hurt my ears. The audience comment cards at the end of the night were littered with raves like “The best thing I’ve ever seen” and “The hardest I’ve ever laughed in my life.” The headliner, Andy, a veteran who had performed on Letterman, a comic who had seen it all, told me it was one of the most amazing things he’d ever seen onstage.

It was the last thing I needed. What should have been rock bottom was just another hero drug story: the time I was so dope sick I puked onstage and still killed.

This excerpt is from the book Float Like a Butterfly, Drink Mint Tea: How I Beat the Shit Out of All My Addictions by Alex Wood. Published by Robin’s Egg Books, an imprint of Arsenal Pulp Press, 2021. Reprinted with permission from the publisher.