A few years ago, at a reading by various authors of various pieces of crime fiction in an unpretentiously elegant bar in Vancouver, one writer began explaining the precise physiology of decapitation. As he told it, the lights of the human mind, powered by the juice of the human brain, didn’t go off the second that the cord was cut. Like the nightmare inversion of the acephalous chicken whose body continues, for a few jerky and frenzied seconds, to perambulate around the farmyard even after the fall of the cleaver, it seems that the human cranium, uprooted from neck and shoulders, can carry on with the business of processing sensations — like terror, fear, bodylessness — for a few chilling moments after lift-off. This, the author explained soberly, is why people are innately afraid of beheading.

Well, clichés are cliché for a reason: you really do learn something new every day. Here I was, blissfully unaware that there was any subtle, subterranean, gnostic reason why people were afraid of getting their heads chopped off. Dumb-dumb that I am, I’d been theretofore gawping my way through life under the mistaken impression that the reason people were afraid of decapitation was because it tended to involve having their heads chopped off.

The principle of the baroquely redundant explanation is perhaps the defining feature of reporting on the Middle East in the Anglo-American world. If someone were to say to you something along the lines of The Irish are always singing, that’s why they hate it when you slash them across the throat or The French love food, that’s why they don’t like getting stomach cancer or The Italians adore the visual arts, that’s how come they get angry if you stab them in the eyes, you would immediately and correctly identify that you were speaking either to an idiot, or else to someone for whom the basic universal humanity of the Irish, French, or Italians was somehow in question.

Yet there is virtually never a news item or editorial — even a putatively sympathetic one — written in English, about the Palestinians, which doesn’t strain to offer some atavistic religious, tribal, or nationalist explanation for what are, on their face, eminently human and, ultimately, conceptually relatable circumstances.

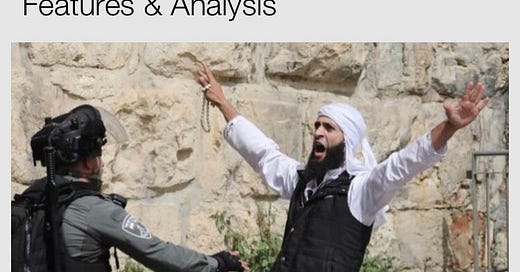

On the BBC website, this week’s headline “Old grievances fuel new fighting” — accompanied, on the mobile site, by the image of an armed Israeli troop approaching a turbaned man clutching prayer beads, his hands thrust to the heavens — could easily throw a reader off the scent of the fact that the proximate cause of the current violence is a set of East Jerusalem evictions of Palestinian families in order to make room for new Israeli settlements, still before Israeli courts.

Ah, yes, the lands of Abraham, or Ibrahim — where brother has turned on brother since Cain slew Abel, or Jacob and Esau struggled in Rebekah’s womb, intones the sensitive, educated, historically-informed reader while some Palestinian widower whose wife died of COVID tries to figure out where he would move his four kids, one of whom was born at military checkpoint, if and when their house gets bulldozed.

Branko Marcetic at Jacobin has done a masterful job of dissecting the combination of selective omissions and use of the passive voice across mainstream media — the same outlets that are supposed to be our own only rescue vessels in the stormy seas of internet disinformation — that have made the recent violence seem like just one more instance of a phenomenon akin to bad weather, fundamentally a matter of too many religions with too much stuff in one small neighbourhood. It’s essentially just monotheistic meteorology, with Jews, Muslims, and Christians meeting and chaos raining down with the same predictability as if a cold front met a warm front above a Canadian golf course — also built on sacred land, as it happens, but not the kind likely to be covered in a world religions class or New Atheist YouTube clip, so usually left out of the scope of the otherwise all-purpose analytical framework. I was envious that Marcetic noted, before I had a chance to, the incredible Orwellian tic this past week, used in too many pieces not to be indicative of some kind of more general rot, to explain the origins of the recent violence as being in a series of “escalating clashes” — which is something like saying I got fat lately due to recent weight gain, or that there is more French being spoken in a particular area because of the growing number of Francophones.

Every piece on the current conflagration is at pains to remind you that Jerusalem is a holy city for Jews, Christians, and Muslims — and that, for the latter, Ramadan is a holy month. A number of them will also point out the semi-secular national symbology of Jerusalem for both Israel and Palestine. And you know what? All of that is true. What is also true is that if you and your family were living in the world’s least appetizing basement suite, in a neighbourhood you fucking hated, in a town you only moved to because of a job you detested even more, you’d still be white-hot enraged if you were evicted so that the thing could be knocked down to make room for the citizens of an occupying power.

Muslims, Jews, and Christians all feel a spiritual claim on Jerusalem? True. I myself was raised in the church and always felt a connection to Jerusalem — having even visited, more than twenty years ago (Benjamin Netanyahu was Israeli prime minister then, too), the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; where, incidentally, I slipped and fell on the floor of the Aedicule, which I didn’t take to be a very good sign. But that’s a different order of belonging, and a different kind of claim, isn’t it? The Onion headline “Palestinian Family Who Lost Home In Airstrike Takes Comfort In Knowing This All Very Complicated” mordantly hints at the ways in which byzantine (not to say Byzantine) explanations are offered for what are, on the ground, very straightforwardly devastating effects. But the theological window-dressing which always accompanies any news of Israel/Palestine actually obscures what are also fairly straightforward geopolitical dimensions to the conflict. Do Muslims, Jews, and Christians all claim holy sites in Jerusalem? Yes. But East Jerusalem is illegally occupied and annexed Palestinian territory. Sure, God may be, in the words of the theologian Paul Tillich, the ground of Being — but the occupation, not God, is the ground of recent violence.

Palestinians don’t live their lives on any more symbolic a plane than you or I do. I am absolutely certain that they do not like being shot at in the compound of a mosque, at prayer time, during Ramadan, any more than I’d want to be shot at during Communion on Easter Sunday — but there are also no better, more convenient times at which anybody wants to be, or will begrudgingly allow being, shot at.

There is a kind of ignorance that comes from looking away from something, and then there’s a kind of ignorance that comes from staring so hard and overfocused that you can’t see what’s right in front of you. You don’t need to understand anything about Islam or the layout of the Temple Mount in order to empathetically process where the despair, misery, frustration, and anger are coming from after decades of occupation, humiliation, and dispossession. You just have to allow, for a few seconds, that like us in North America, or like their neighbours in Israel and Saudi Arabia, Palestinians are human beings too.

Yes