One awkward inevitability in the life of a comedian is that at some point — and from both sides of the equation — one will have to sit or stand beside another comedian, with whom one has just finished a show that went asymmetrically well for one of you, but just as poorly for the other, and politely entertain feedback from the departing crowd.

The best (and worst) version of this story I ever heard was shared with me by a well-known comedian whose stars had aligned many years earlier one night on the road to produce a perfect show, without extending the evening’s graceful mojo to his colleague for the gig. On the way out, an audience member stopped to ply the shining comic with plaudits and compliments, before realizing on his own powers the embarrassing unevenness of his praise. Searching for something positive to say to the tough-luck performer, the guy from the crowd quoted back the one line he could think of from the act which had gotten a big laugh. Which would have been fine, except that this particular line had been given to him by the other comedian as a suggestion the night before.

The second time I wrote the script for a local-colour comic children’s play, Cinderella: An East Van Panto, there was one joke in the book that stood head and shoulders above all the others. It was, without exception, the biggest laugh of the night, because it was objectively the funniest thing in the play.

At the very moment when Cinderella stood poor and bereft and definitely not going to the ball without some sort of supernatural intervention, the curtains pulled back to reveal her deliverance in the person of a fabulous sparkling lady in resplendent drag, with a large oceangoing ship growing out of the southern hemisphere of her body:

The BC Ferry Godmother.

Anyone — anyone — who saw the play and offered me any positive feedback on the writing isolated this moment as particularly worthy of praise. As a joke, it was exactly what the show was supposed to be about: hyperlocal, gently subversive, clever but broad. BC Ferry Godmother, they would say slowly to me, shaking their heads, mock reproach in their voices as though I’d been sitting on the line, hiding it from them, waiting to deploy it for maximum explosiveness. I ran into a local television journalist who had defined not only broadcasting excellence but also poise and elegance from the time of my childhood; this was a person I could never in my life have conceived would ever even know my name, and now here she was, fresh from seeing a play I’d written the script for, saying, “BC Ferry Godmother…”

Every polite smile I returned was half wince. It wasn’t just that the moment was not exclusively mine to claim triumphantly, belonging just as much to the performer, costume designer, set designer, lighting engineer.

It was that “BC Ferry Godmother” was something an actor had said, seemingly by accident, at a read-through of the play’s first draft. It wasn’t mine to claim triumphantly even a little bit.

Specifically, the actor was performer-playwright Jonathon Young — who wasn’t even in the show. Filling in for an actor who couldn’t be there, Jonathon miraculously “flubbed” (I still think it was most likely a camouflaged act of inspired generosity) the Fairy Godmother’s introductory line, and director Ami Gladstone quietly leaned over to me and whispered the inevitable: “Well, that’s going in.”

All of this was about seven years ago give or take, and so what brings it to mind now? Because I’ve finally made peace with the fact that I didn’t write the best bit of writing in my script.

How? This past weekend, I learned that Fat Clemenza’s infamously homey post-execution sangfroid, delivered in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty in the first instalment of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather — “Leave the gun, take the cannoli” — was half an ad-lib.

The magnitude of this discovery is perhaps best conveyed by the fact that I learned it in a magisterial newish book about the film, considered the last word on the production, and titled Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli: The Epic Story of the Making of the Godfather.

I was a teenager when I read Mario Puzo’s original novel, and I’ve never read he and Coppola’s screenplay — but I’d just assumed that Clemenza’s perfect line, a metonym for practically everything important in the story, had to be in the source material; the idea that it isn’t is a vertiginous one. Mark Seal, the author of Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli — whom as you can probably guess, feels a certain attachment to the line — is quick to point out the thematic heavy-lifting done by the six little words. They speak volumes on violence, patriarchy, immigration, family, and more.

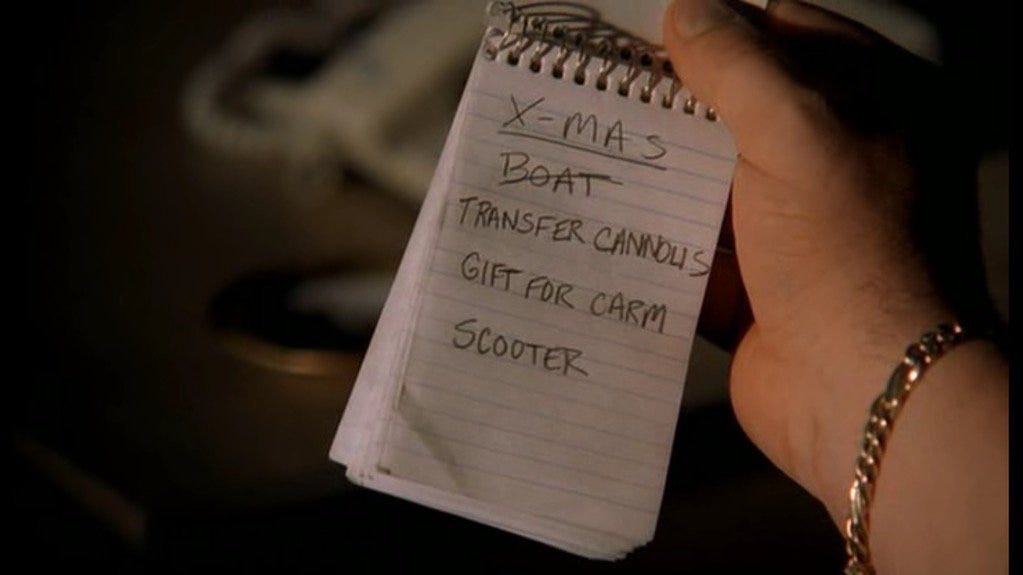

Beyond that, the line has shaped the texts that built on The Godfather as ur-source. On The Sopranos, Freudian subtext became text itself, as “cannoli” was used alternately to refer to Tony’s money and his penis. In one episode, a to-do list including the pressing need for moving around large sums of illegal cash reads “Transfer Cannolis.” But the real transference comes when Tony has a sex dream during which he receives fellatio from an unseen woman under black silk sheets; he wakes in terror when his psychiatrist’s face emerges, and says (in the voice of his mistress), “Tony, I love your cannoli.”

According to Seal, actor Richard Castellano’s scripted line for Clemenza’s Godfather scene was simply, “Leave the gun.” which is a bit like finding out that the Mona Lisa was originally supposed to be eating a meatball sandwich, before the guy who was framing it playfully sketched out a smile.

If the best line in one of the greatest films ever made was improvised, I can live with BC Ferry Godmother.

By the close of his long career, the American theologian Gordon D. Kaufman had landed about as close to atheism as one could while still laying claim to a nominal religious identity. Many believers, of whatever faith, might have had a difficult time distinguishing between Kaufman’s brand of religious naturalism and simple, straightforward secular disbelief.

But for Kaufman, the hard kernel of divinity in the cosmos was the reliable presence throughout the universe of “serendipitous creativity.” We are not bound to mere mechanical repetition but instead open to and drawn by novelty, complexification, and fecundity.

I figure that, by this logic, to labour painstakingly over the product of your own brow is human; but to let someone else blow it wide open for you, half by accident, is Divine.